The reasons to love bookstore-cafés is that you get a chance to discover new stuff to read. The reason to hate my particular café is that, every week, even when I ask for a *normal* coffee, the waitress continues to regurgitate the same phrase: "will that be a large of a small?" Anyway…

The reasons to love bookstore-cafés is that you get a chance to discover new stuff to read. The reason to hate my particular café is that, every week, even when I ask for a *normal* coffee, the waitress continues to regurgitate the same phrase: "will that be a large of a small?" Anyway…

I read a nice article in the New Yorker today, about a stressed out restaurant-entrepreneur called David Chang, who runs several noodle-bar-styled restaurants in New York City. The Yorker's articles are always so long, but it was a captivating article. I took some notes, which I'll share with you now.

- Waiters make way more money than chefs, simply because of the tips; the figure mentioned was $1700 per 32 hours vs. $350 that chefs make. Turning chefs into waiters, which seems like a logical decision in a noodle-bar, comes with the challenge that these types are not always that domesticated (can't help thinking about Chef! here).

- The front-end of a restaurant—servers(?), the set-up, beverages—is relatively simple (compared to the work that goes into cooking) and can be consolidated across multiple restaurants.

- Personal integrity in cooking—e.g. cutting fish-cakes properly, even though the customer won't notice them in a bowl of ramen—is the difference between a quality-restaurant and a McDonalds or Uno.

- Standards: A piece of chicken can taste wonderful to a customer, he won't know why, but it's actually because it's been prepared (marinated, dried, etc.) for more than 24 hours.

- Quote: "The great thing about fast-food is that you could sell out without worrying about it, because fast-food isn't pretentious and selling out is in the nature of the business."

- Quote: "Cooking is honest work; gives you a way to measure yourself."

The thing about restaurants is that I'm painfully ignorant about so many things going on in that world. Cuisine is like art—it's dynamic and filled with critics. For instance, there's the "foam" trend, mentioned in the article, hot in the 90s, but which I never heard off.

For me, I'm always interested to find out more about this industry, because I want to be part of something that produces culture. But I'm constantly thinking about whether it's wise to enter such an industry without a basic familiarity. It would be like me entering the tech-industry, without being aware of open-source, how to write code, or do project-management; it's just not done.

Food for (mostly, my own) thoughts.

Filed under: cooking, culture, entrepreneurship, food, horeca, human resources, operations, Research, restaurants, retail, vision

The reason I like Star Trek, most sci-fi in fact, is because of the space-opera aspect. You don't just tell a story, you design a universe around it. I've been a fan of the show, ever since the age of 10 when I got to watch TV at home. In some ways, sure, the time spent watching the show impoverished my life by taking me away from other endeavours, in other ways, it enriched it by contributing to my ability to dream.

The reason I like Star Trek, most sci-fi in fact, is because of the space-opera aspect. You don't just tell a story, you design a universe around it. I've been a fan of the show, ever since the age of 10 when I got to watch TV at home. In some ways, sure, the time spent watching the show impoverished my life by taking me away from other endeavours, in other ways, it enriched it by contributing to my ability to dream.

As I grew older, I started paying much more attention to the story-telling aspects of the franchise. For instance, did you know that until the second season of Star Trek, the next generation, the writers didn't create a place for the crew to relax? It was only then that the makers came up with the concept of Ten Forward, hosted by the infamous Guinan (see pic). Later, in its spin-offs, Deep Space Nine and Voyager, we also saw a big role being played by the "lounge", hosted by Quark and Neelix respectively.

It was felt that by introducing this aspect into the show, a third place, it allowed the characters to show a different side of their lives, necessary if you want to teach a complete philosophy about society, as Gene Roddenberry was in fact doing. And of course, it spawned plenty of dramatic stories, that would otherwise never have happened. It allowed for romance, friendship, and conflict to happen, for aliens to meet and interact with one another.

What's interesting about the franchise that each series had a different archetype, which also affected the room for "drama." You could see it as both an evolution and devolution of a story. Star Trek, the original series, was the raw outline of Roddenberry's philosophy about the future of society. The next generation was much more developed and allowed for deeper interpersonal relationships. Deep Space Nine was again an evolutionary step, and much of the stories centred around "life" on the station.

Both Voyager and Enterprise represented a devolution. Voyager introduced the "morale officer", in my opinion, an engineered effort to bring a certain warmth to the story. But it was much less about teaching philosophy, as it was about survival. It showed that Roddenberry's universe was in fact small and could break apart at the edges. But it was still a good story.

Enterprise represents a return to those raw ideas. Perhaps it was felt that the franchise could cover no more new ground, and that a new philosophy had to be designed. It was also a story of survival and the raw pioneering spirit, shown in part in Voyager. But it felt like a military mission, there was little room to form complete characters. Instead we were presented with deep dramas, echoing the 9/11 events, which turned the characters into one-dimensional creatures, much perhaps the way the news depicts the main characters involved in the post-9/11 era.

To me, at least, Star Trek is a good analogy for certain principles in life. That it is not enough to search, but also to build. That friendships and societies are built, not only from the hard work they require, but from the breaks we take to reflect on our actions, and the places that are engineered to cater for that need.

Food for thought.

Filed under: culture, design, entertainment, horeca, interlude, media, Politics, retail, self-development, third place, trends, vision

Marqt is a market for farmers, recently launched in Amsterdam by Quirijn Bolle en Meike Beeren (both ex-Ahold). Can't really sum it up much more than that.

Marqt is a market for farmers, recently launched in Amsterdam by Quirijn Bolle en Meike Beeren (both ex-Ahold). Can't really sum it up much more than that.

It focusses on two opportunities: from the supply-side, many farmers want to sell their products, but are unable to because of the power-play from regular retailers and/or at relatively low profit-margins. Last year, when I briefly looked at the organic boom, I already thought that there is an opportunity here, for farmers to become retailers themselves.

This is made possible by the other part of this equation, an elevated demand by customers for natural and ethical produce, and, to a lesser degree, local produce.

Bolle and Beeren rightly identified an absence of identity in food-retailers, an absence of accountability for the product-decisions they make. But they also identified a need by consumers for quality-guarantees.

Because you have to wonder, how is Marqt different from the regular outdoor-market that exists in every city? Well, here's one difference, and I'll try to give an example. 'Tis the season of mangoes, and I'm hooked. I've been buying these babies at €1 a piece at my supermarket, but stumbled across some great deals at the local market: €2.50 for a box of 8! The only problem: about 6 of these were either unripe or overripe. And who do I complain to? One of the 100s of vendors on the market, whose name or brand I don't even remember?

From my understanding (I don't live in Amsterdam), Marqt-products are more expensive than those of local markets, about on par with regular supermarket-foods. They work with partners that are able to supply in greater numbers, offer a quality-guarantee, and, very interesting, train Marqt's staff to understand and explain how products work.

Their added value is that they can offer suppliers higher margins, and consumers a richer shopping-experience. And from what I hear, though I have no numbers, the store is doing reasonably well.

Two other interesting facets: Marqt houses individual suppliers' stores. So you have Store X for dairy, store Y for meat, and store Z for bread. Marqt provides the space, the staff, the marketing, and collects a percentage of the profits.

Also interesting: the store doesn't accept cash. It's progressive, I agree, but also great marketing-value, sure to raise an eyebrow or 1000. And it saves money on the back-end, though I hope they get rid of the €0.50 transaction-fee.

I think it's a great idea, and hope the store continues to do well. Gives me hope, both in terms of opportunities for retail-entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurship in the Netherlands in general, which (in my opinion) could use a boost.

Filed under: branding, business strategy, community, culture, entrepreneurship, farming, food, Health, Marqt, organic, retail, supermarkets, trends

Witness the following. A bar that comes in various flavours: chocolate chip, dark "luxury" chocolate etc. Yumm! It's cheap, costs around $1.50 per bar in the local drugstore, currently. And it contains 32 grams of protein. The perfect post-workout snack, it seems.

The only problem? The body doesn't digest it well at all. There are times when it sits in my stomach like lead, and other times, when my body can't wait to get rid of it. Empirically tested, two out of two times, that is what happened to me. Just last night, I woke up at 3 a.m. with a stomach-ache because of that damn bar.

Are snacks doomed to be unhealthy?

Back when I was a vegetarian for a brief two years, the one thing I missed was to have a snack that did not contain either an overdose of sugar, of fat, or of bread. With the exception of perhaps a nut-bar, a fresh juice, or chewing gum, those are pretty much your choices, walking down a street:

- A chocolate-bar: high in fat & sugar

- A burger, sandwich, or a pizza-slice: high in fat, starch, and limited protein

- Fries or chips: high in starch and fat

- A carbonated drink: high in sugar (excl. the light versions) and extremely bad for your teeth

A new era?

Interestingly enough, due to external pressures, I hear that certain supermarkets are changing the layout of their stores, removing snacks and junk-items from the register, and replacing them with healthy options like fruit. Equally interesting, (forgot where I read this) they are expecting a multi-million euro loss because of that policy.

Certain tricks do seem to work in raising those profit-margins. While a kilo of regular apples currently costs around the €1.50/kilo mark, pre-peeling and -cutting those apples, raises that price to ca. €8/kilo. Ka-ching!

The argument for mass-production is that it enables innovations to become cheaper and hence raises the general quality of life of consumers. The argument against mass-production is a more controversial one: that it destroys the unique quality of, let's call it, art.

The argument for mass-production is that it enables innovations to become cheaper and hence raises the general quality of life of consumers. The argument against mass-production is a more controversial one: that it destroys the unique quality of, let's call it, art.

Starbucks is a very good example of those principles. It brought a higher standard of coffee to the American masses, who, according to Howard Schultz's Starbucks biography, had long been oppressed by low-quality coffee from retailers and coffeeshops alike. At the same time, as the recent crisis at Starbucks illustrates, it has reached a saturation-point: it has brought Starbucks-outlets to every corner in the US, as well as spawned a whole army of competitors, and its brand has become diluted. It has become a commodity.

Back to their roots?

The re-enstatement of Howard Schultz as CEO is a signal, that the business has lost some of its original spirit and is in need of a guiding light. A letter that is rumoured (!) to be written by Schultz confirms that Starbucks will be focussing on re-introducing that original spirit, as hard as that will prove to be. There's only so much that you can change, after your company has reached a certain size. It would, at this point, be like saying that McDonalds is planning to become your corner-restaurant where everybody knows your name and favourite food.

The innovative angle

A friend of mine made me aware of a new coffee-brewing machine on the market, called Clover, which promises to deliver a higher quality coffee to consumers, though also at a higher price. According to Bruce Milletto, a retail consultant to the coffee industry, "a typical American café spends around $50,000 on equipment, about one-quarter of which goes on an espresso machine. At $11,000, a Clover costs the same again." Thus the investment-proposition is not an attractive one to the average cash-strapped café, who would have to spend that kind of money and charge an expected $6 per cup to recuperate that cost.

Following the rules of mass-production, Starbucks + Clover makes for a match made in heaven, and so it is: Starbucks has in fact acquired Coffee Equipment Company, the four-year-old Seattle-based maker of the Clover coffee brewing machine, for an undisclosed sum.

Considering that Starbucks has long been threatened by the commoditisation of coffee in the US, through the birth of literarily 1000s of new franchisers who, on the surface, provide the same value-proposal, though perhaps at a lower quality and price, it makes sense to acquire one piece of machinery that makes a bit of difference in the eyes of certain consumers. Considering the recent partnership with Apple, I believe that these consumers share a similar taste and price-insensitivity, and since that segment appears to be growing, I believe that Starbucks made the right call. They appeal to the type of customer that will pay $6 for a cup, and with their economies of scale, that price is sure to drop to a slightly more acceptable level of (I guess) ca. $5.

The cultural angle

There is another side to this. The USA is not the world, and while Starbucks has been thriving over there, the Europeans (I can't speak for other continents) have enjoyed a coffee-culture for quite some time. For people like my parents, who are respectively citizens from Southern- and Western-Europe, and avid café-visitors, they would not even consider going to the Starbucks in the centre of their German hometown, because there are plenty of alternatives with more atmosphere, more identity. To them, Starbucks is like a McDonalds, a franchise that in fact shares many cultural values—bringing a good to the masses—and does so by building ecosystems of services—from music-retail to the happy-meal—to deepen the (commercial) relationships with its customers.

Consciously and subconsciously, I'm a sympathiser of "unique" café-outlets. I like spending time in them, sometimes hours at a time, read my newspaper in peace, and enjoy a reasonably good coffee at slightly less than $2 a cup. I don't actually care about spending twice that for a coffee, but all the Starbucks's I've been too (exclusively in Germany and the UK, I must admit), have been so devoid of atmosphere that I don't really spend more than a few minutes there, 30 max. The only thing that does attract me about them and similar stores, is that I can grab a cup-to-go, mostly in the summer, and enjoy it out in the sun.

As a citizen of Europe, I think I am a fan of the heritage of the traditional café and don't really want it to go. If that makes me "backwards" or conservative, I am sorry. I want the chance to enjoy a Turkish coffee in Brussels, an Italian coffee in Cologne, or simply a Dutch one here in Rotterdam. I enjoy knowing the history of a pub that has existed for over a 100 years in Antwerp, and the same in Maastricht, or Amsterdam. I want there to be a diversity, and most important, I want that choice to be mine. I don't want there to be a cloned coffeeshop on every corner.

One of the saddest things I heard, while I was in Belgrade last year, was the exactly such a historical café was replaced by a chain (and the coffee stunk too); and I was equally sad to see that nearly all of the traditional retailers I remember from before the war had been replaced by a cloned shopping-centre that would've made any Western city proud: from H&M to Footlocker.

Opponent: Starbucks?

Globalisation is a situation we must all deal with. Its oldest proponents are the FMCG-companies, who are focussed on producing the same good for millions of people. The question is whether coffeeshops should embrace the FMCG-principles like McDonalds and Starbucks clearly have.

Starbucks is a formidable opponent: it is both a roaster, a retailer, and an FMCG-producer. It is strong in the US, and has a significant presence in the rest of the world. It will not go away, And not all believe that their presence is all that disruptive. I don't either, as long as Starbucks knows its limits. There are parts of the world that do not share the same qualities as US-towns. Some cities have long histories and places of heritage that should perhaps not be housing a McDonalds or Starbucks.

In a way cafés are stuck. They need the kind of innovation that Clover brings, but they are not in a position to buy their way in. If they did, they too would have to become mass-marketeers, in order to recuperate that cost. Instead they need to focus on what they do best, and coffee-machine makers to do the same and just license their technology. And whether the latter is able or willing to do that is the question.

I'm not sure how much Clover was acquired for, no one is. And I'm not sure how far Starbucks is willing to go to ensure their qualitative and quantitative dominance of the market. Will they grab every new piece of technology that promises to introduce a higher quality of coffee to consumers, keep it for themselves, and leave the traditional cafés to differentiate themselves simply by their "culture"? Sheer business-principles dictate that they will.

Howard Schultz made me believe, in his book, that it was Starbucks' mission to bring better coffee to the world. Let's hope that a richer coffee does not come at the price of a blander world.

This piece is in fact incomplete. Optimally I should write up a list of actions for coffeeshops to take. However, I am not yet that familiar with all the business-issues facing these organisations and all of my suggestions would be targeted at growing in size and battling on similar terms as a national or global player. And I'm pretty sure that many would not be willing to do that. So I think I'll wait until I have a more objective grasp—from all angles—on the situation, before giving practical advice. Feel free to provide me with that objectivity through your comments.

Filed under: branding, business strategy, café, catering, coffee, culture, ethics, Globalisation, innovation, retail, starbucks, technology, trends, vision

Funny how moods influence musical preference. Last week on my run, I would've told you that Junior Jack is the sh*t; a few weeks ago, on a lonely walk through a misty and deserted street, it would've have been Lisa Gerard's haunting voice. But last night, as my eyes were feeling heavy with sleep, it was Grant Green that touched me most.

I first stumbled on Mr. Green's music after trying to prove to my brother that many rap-songs are sampled from other (better) songs. Turns out Grant Green performed a song, named "Better Tomorrow," that was later sampled in Dr. Dre's hit-song "Still DRE." Even though it's not my favourite track of Green's, it's one of the few I could find on YouTube. So here you go, a very recognisable melody after 1:20 mins.

P.S. The Grant Green album I like the most, is called "Ballads."

Addendum

Thanks to the power of Mixwit, you can listen to a whole playlist of Grant Green songs, sourced from all over the web. Enjoy!

Filed under: entertainment, interlude, media, music, retail

Just read an interview with Ford's ex-CEO Jacques Nasser on the training programs that were prevalent at that time (2000). He justified their need, by outlining the history of the car-industry between 1905 and now.

Just read an interview with Ford's ex-CEO Jacques Nasser on the training programs that were prevalent at that time (2000). He justified their need, by outlining the history of the car-industry between 1905 and now.

- 1905-1920s - colonisation of car-companies: smaller replicas of car-factories in the US were being built abroad. Hardly any competition.

- 1920s-1950s - nationalism: lots of countries were building their own national vehicles. Competition mostly on a regional level.

- 1960s-1980s - regionalism: the rise of trading-blocks (NAFTA, EU, etc.) and as a response the functional/regional division of companies.

- 1980+ - globalisation: global competitors, more markets, more divergence of consumers, more need for people/ideas/growth.

The situation at Ford

The result of the last period is that there are more Ford-people around the globe to manage, that more markets need to be served with different needs, and that the company that can generate economies of scale & scope, while being most consumer-orientated wins.

Two strategic priorities are at play here: consumers only see a part of the car, which means that the hidden qualities can be mass-produced; and consumers value those qualities most matched with their environment—e.g. in Brazil, so I read, roads are abysmal (if any Brazilian reads this, correct me), and good suspension is highly valued. In China, luxury models are mostly driven by chauffeurs, while the consumer sits in the back, hence he/she values luxury in that part of the car.

In this scenario, two types of qualities are valued with people: to understand the corporate qualities of Ford and make decisions that favour its mass-market strategies; and those that understand the local environment and can design car-offerings tailored to local needs.

Social operating mechanisms at Ford

Ford, at the time of the interview, had about 12 programs aimed at promoting these skills. The ones mentioned, included: Capstone, which is aimed at (24) executives; Executive partnering, aimed at (12) promising managers; Business leadership initiative, aimed at the whole organisation; and a weekly email-newsletter, called "Let's chat about business," also aimed at the whole organisation.

Methods + Aims were:

- Team-building - to get people to work more closely together / develop a corporate culture

- Teaching - to get people to understand the priorities at a corporate level, rather then just at a divisional/functional level

- Projects - to get people to come up with problems plaguing their organisations at that time and develop creative solutions to them.

- Shadowing - to develop leaders

Thoughts

Several thoughts going through my head at the moment. I am both uncertain how relevant this is to the SME-environment, and at the same time I do a lot of "social engineering" and can certainly think of a few cases in my past where a certain structure would have benefited the small teams I worked in. I'll probably write a third post about the SME-perspective at some point in the future.

My favourite way to picture "social engineering" however, is through designing processes that bring elements of the organisation together with customers and "raw-inputs" (new technologies, future employees, and partners, etc.). Maybe, I'll write about that at some point too.

Of course, I always appreciate the reader's perspective on this. Social programs at an SME-level, good for team-building or bad because it distracts from survival-priorities?

The picture is courtesy of articlescaravan.com

It's about a week before my birthday, and (Dutch) T-Mobile, as they do every year, decided to send me a gift. And, just like every year, I pretty much throw it out a minute after opening it. This year it was a pink tablecloth with joyful crap written all over it, last year I think it was an inflatable window-decoration, pink also, and I don't remember what it was before.

There's two reasons, why I respect T-Mobile's gesture: one, they make an effort and I appreciate the gesture; and two, they combine their gesture with marketing, which I respect from a business-standpoint.

That said, everything else about it is idiotic. I'm 30 years old, they know this, and I'm seriously not considering using a pink table-cloth. From my phone-patterns, they should also know that I'm not planning on throwing a big party. Had they bothered to do a simple Google-search, they would have known I run a few blogs and decided that this would be a better way to reach me.

They should have given me free cinema-tickets instead. Their marketing-value from the table-cloth is zero because I won't show it to anyone, and am instead calling them tasteless.

If they had given me a cinema-ticket, I would have maybe scanned and pasted it all over this blog, thanking them. At least a 100 people would've read about it and thought about subscribing to T-Mobile. Instead all they now see is this:

Welcome to the internet, T-Mobile.

Filed under: marketing, retail, technology

I decided that the one thing that was missing, for myself, on this blog, was the "fun" post, where I could write about the softer side of sounds + food & retail. The other two sides, facts & opinion, are also areas I plan to develop on, but without fun, there's no balance. Therefore, I am re-instating the interlude, but trying to not exaggerate, like I did during my thesis-break.

The reason to like fiction, I guess, is because, unlike the mechanics of business, its dreamlike qualities encourage the viewer to think abstractly. And abstract thoughts, to bring it back to business, lead to creative ideas that no-one had before, and have the potential to create market-spaces, no one imagine before that. At least that is my theory.

Two of the following movies are quite surreal: one is about adulthood and the other about childhood. They are both about creativity, about dealing with the demands of real life, and about embracing your passions.  "Where the heart is"

"Where the heart is"

A typical 80s flick, where the characters are misaligned with the hard-cruel "real" world. In this case, the two beautiful daughters (Uma Thurman and Suzy Amis) and one son (the guy who plays McKay in Stargate Atlantis, if that means anything to you) are disowned by their wealthy father and placed in a broken down house in the middle of the business-district. What I liked about the film is that the house becomes a place of self-expression, and each individual that inhabits it is an artist of some kind. The father eventually loses all his money also and ends up living in this house, and he comes to accept that the world doesn't revolve around money, but around believing in what you do. A light comedy with some deeper principles.  "Mr. Magorium's Wonder Emporium"

"Mr. Magorium's Wonder Emporium"

Here's an interesting exercise: Get a block of wood, as bland as possible. And believe in it.

The weird thing about it is that the block of wood is you. Anything can happen to it, as long as you believe in it. The block may initially appear lifeless, but it is your faith and work that makes it more than its parts, so to say. And that block can be anything. A piece of clay that you turn into a sculpture, a room that you turn into a living thing, an idea that you turn into a business. All it takes is a little faith.

Well, that is the extent of my learning from this film, which was really about a toy-shop that is alive and a girl, Natalie Portman, who refused to accept it was her destiny to run it. It's entirely not meant for my age but I enjoyed it nevertheless.

That's it from me this week, I'll be spending this Easter with my family. Have a good one and until the next time!

Filed under: career, cinema, design, entertainment, interlude, retail, self-development

Ran Charan, who I wrote about a few days ago, made another excellent contribution to my thinking (and hopefully yours), the concept of "social operating mechanisms." He defines them as mechanisms that synchronise individual contributors' efforts.

Ran Charan, who I wrote about a few days ago, made another excellent contribution to my thinking (and hopefully yours), the concept of "social operating mechanisms." He defines them as mechanisms that synchronise individual contributors' efforts.

A step back

Individualism vs. collectivism represent two personality-types. There are the managers, who are integrators and bring both groups together and (are supposed to) identify with the greater purpose of the organisation: maximisation of profit, etc. And there are individual contributors, who through their own efforts bring forth new data and growth, etc. These types are not always suited for management, as they need that freedom to be creative.

Social operating mechanisms fit within the framework of execution, in the sense that that is one of the last stages in a multi-stage process. As the leader/problem-solver of an organisation, you start by identifying a problem; you come up with a set number of fundamental priorities to solve the problem; and you (design social operating mechanisms to) spread that solution throughout your organisation.

An example

Mr. Charan mentions a number of examples, but (for obvious reasons perhaps), I like the Wal-Mart one the best.

- In the early 90s, every Monday to Wednesday, ca. 30 regional managers visited 9 Wal-Mart stores and 6 competitor-ones, to check if Wal-Mart's strategy of offering lower prices than the competition was being implemented correctly.

- Every Thursday-morning, Sam Walton conducted a 4-hour session with a group of 50 people, including those regional managers, buyers, logistics- and advertising people to discuss the status quo, what was going right and wrong, and the future.

Making it relevant?

If this seems like a big-company problem, maybe so. But even on a smaller scale, you could see a similar process happening in the week of a franchise-owner, I discussed a few weeks ago.

As soon as an organisation grows beyond a few people, the barriers between your customers and the leadership of an organisation increase. The politics can be frustrating and are one of the main reasons why original founders leave. The Amazon-story, which I wrote about a while ago, and which also discusses of how Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon tries to keep in touch with the core-principles of Amazon, is also an example of a social operating mechanism.

Naturally, today's reality is somewhat different from the time (2000) that the book was published. We have "the internet" now, which should make creating social mechanisms a much easier to solve. I say 'should' as opposed to 'will,' because it still requires the necessary cohesion, which many technological solutions (in my opinion) are still lacking.

It still comes down to designing people-processes which help you implement core-priorities, and having the tolerance for, let's call them, idiotic decisions that sometimes come from the type of group-think often prevalent in organisations.

The picture is courtesy of infed.org

Filed under: Amazon, books, business strategy, career, community, culture, entrepreneurship, human resources, management, operations, Politics, retail, vision, Walmart

I'm currently reading "What the CEO wants you to know," by Ram Charan, and it's safe to say that it belongs in the top 10 business-books, I've ever read. It's only 140 pages short, but filled with advice that is extremely easy to digest, that I'll be sure to re-read it several times later on, and can warmly recommend to others too.

I'm currently reading "What the CEO wants you to know," by Ram Charan, and it's safe to say that it belongs in the top 10 business-books, I've ever read. It's only 140 pages short, but filled with advice that is extremely easy to digest, that I'll be sure to re-read it several times later on, and can warmly recommend to others too.

One chapter in the book struck me particularly, on coaching, as I consider it a vital skill in business-relationships. Although I think Mr. Charan paints a bit of a rosy picture, I consider it a good standard to aim for. Some quotes:

How would you feel if someone gave you positive feedback on the things you're doing well and specific suggestions for building your skills? Chances are you would feel that you had a personal coach, someone who wanted to hep you succeed. You would feel energized. I can tell you from experience that it works. You can do it for those who report to you, and in the process, you will expand your own capacity.The chapter also goes into a number of examples from real life.

…

Coaching is not a performance review. It's not about what someone did last year, and it's not about money. It's very personal. You're hitting the person between the eyes. You're helping him face his blind sides and learn to do things better. The feedback has to be honest and direct. No sugar coating.

…

Self-confident, secure leaders love to give true feedback because they know that growing people is their responsibility. By true feedback, I mean saying what they really think. Too often, people hesitate because they know they may be wrong, or that they feel reprisal. But chances are your instincts are correct, and they'll improve over time. I've seen numerous times that when you put experienced businesspeople around a table and they talk candidly about an individual, the judgements converge very quickly. It's not had to zero in on the most critical thing the person needs to improve.

Some people say this kind of coaching is a good idea, but their company doesn't have the ambiance for it. Still, you can start with three of four people who would be receptive for it.

Charan's book is all about understanding business principles and setting a limited number of fundamental priorities to improve a business. Coaching is a logical extension to that, as when you clearly communicate what the business priorities should be and how that individual can get there, that's essentially coaching (and makes your life considerably easier in the process).

The author also co-wrote a book called "Execution," which I haven't read, but based on this book, believe is a good choice if you need a more modern read. "What the CEO wants you to know," is from 2000, but I consider it timeless advice.

Filed under: books, business strategy, career, community, culture, human resources, management, operations, Research, retail, self-development

I'm still "on a break," but stumbled across this interesting titbit from a book on warehousing-practices. If you don't like reading lists, too bad because it's interesting, but I've also summarised the key-points in the end.

I'm still "on a break," but stumbled across this interesting titbit from a book on warehousing-practices. If you don't like reading lists, too bad because it's interesting, but I've also summarised the key-points in the end.

China

- Low labour and land-cost, but high equipment costs, translate into large (e.g. 250,000 square feet), low warehouses like in the US, but often lacking even a forklift.

- Certain goods like consumer electronics, are of such high value, have a short life-cycle, and thus a lower inventory-cost, that expenditure in state-of-the-art technology is justified.

- Certain cost-saving practices, like removing the pallets from shipments in order to ship more goods, cause some inefficiencies other countries, like, eh, re-adding pallets.

East Asia

- A traditional focus on personal relationships and less on computational models, means there's a lack of data and opportunities for improving performance are not well-developed.

- The most active economic areas are separated by lots of water, which means lots of product conveyed by air (for high-value or time-sensitive products) or ship (for bulky items or commodities). The high costs associated with this, are incentives to consolidate freight.

- Therefore, more strong regional hubs, like in Hong-Kong and Singapore, are expected to emerge.

Europe

- High labour-costs and an inflexibility of the work force have lead European warehouses to be more advanced in terms of automation.

- A growing common market will also lead to more economies of scale in the future, leading to larger, centralised warehouses.

India

- Characterised by cheap labour and land-cost, but relatively expensive capital costs (machinery and the like) and an underdeveloped infrastructure (both physical & administrative).

- The markets being supplied are generally local and not very wealthy, which leads to the SKUs not being high cost and there being little incentive to increase efficiency through capital expenditure (IT).

- Global demand means that larger distribution centres are being built around large ports like Mumbai (Bombay). The lack of land there is leading to high prices, comparable to Singapore/Hong-Kong.

North America

- Characterised by a culture of mass-consumption and a uniformity of the market and distribution infrastructure, which translates into large centralised warehouses and accelerating rates of product flow.

- Warehouses are often situated in the countryside surrounding metropolitan areas, which is cheaper, while being well-connected.

- A good telecommunications-infrastructure enables better supply-chain co-ordination; Warehouse management systems are generally advanced, and the rich data leads to better tracking and performance.

- High labour-cost are off-set by using cheaper migration-workers

Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan

- Due to a lack of land and high labour-cost, warehouses tend to be built high.

- Elevators are one bottleneck, caused by this style of building, however a Singapore warehouse has found a solution to this: A multi-floor facility with no automation or elevators, but, instead, a spiral truck ramp so that trailers may be docked at any floor (see pic). This does claim more land area, which must be recovered from above, and doesn't work well if trucks have to shuttle between multiple floors.

- While both Singapore and Hong-Kong act as hubs, Singapore is much more international, receiving goods from manufacturers all over Asia and shipping it to other countries; Hong-Kong receives mainly Chinese goods. Also, for the latter, many of the goods come in via trains and trucks, while leaving by ship or flight, while for Singapore it comes and leaves via sea and air.

South and Central America

- Labor costs are low, though not as low as in China, and the nature of its local economy and customers does not justify high equipment expenditure.

- The only exception is Mexico, which can quickly ship products to the US and keep its inventory low, thus justifying state-of-the-art technology.

Final thoughts

Some general conclusions can be drawn.

- Labour costs are a factor when considering automation; automation is a factor when considering optimisation; optimisation is a worthwhile expenditure when dealing with high value goods with a high velocity.

- Cheap land seems a fundamental advantage, looking at the logistical nightmares that Singapore and other high-rise builders must be experiencing.

- Access by land will significantly decrease the cost of transport. Generally, a well-developed infrastructure means more access to wealthy markets and enables warehouses to store high-value/high velocity goods, which is good for them.

The book 'WAREHOUSE & DISTRIBUTION SCIENCE,' which is available as a free download, provides some incredibly detailed info on how to effectively set up warehouses and distribution chains. Well worth a glimpse, if not more.

Filed under: Asia, business strategy, culture, design, Europe, Globalisation, human resources, innovation, logistics, operations, real estate, Research, retail, RFID, supply chain managment, technology, trends, USA

Should the platform for interacting with your customers be "open" both ways?

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 12:00 PMThese next few weeks, my posting-rhythm will slow down due to personal issues, sorry about that. It does however feed into this topic here.

Premise: A couple of things happened these last few days, which I think are noteworthy. The Zuckerberg-interview on SXSW got slaughtered by the twitter-crowd (though there's a human behind every trigger), and which is an example of a BAD interview. There's Steve Balmer, who came across as both human (sympathetic) and capable, an example of a GOOD interview. And there's John Battelle, who wrote two good posts on that every business is a media-business and every business should find a way to engage with its customers.

It's all about PR of course, and somehow some people got it into their head that social media—blogs, social networks, web-sms (my term for Twitter, Pounce, Jaiku,etc.)—is a good way to relate to the public. The problem, if I may call it that, is that these are two-way conversations between people that are essentially observers: users + media. And that, as the Zuckerberg-interview shows, when users + media get angry, they get ANGRY. Now, you could argue, bad publicity is still publicity, I just consider it disruptive.  Business, in my opinion, is two things: a machine that produces output, and engineers that seek to optimise the machine and increase its output. Arguably, user-feedback is useful for tweaking the machine to perform better, and optimally get more users to purchase its output. And outward PR (marketing) also means that more people are aware of your great machine and want the output. Ah, machine-analogies, gotta love them.

Business, in my opinion, is two things: a machine that produces output, and engineers that seek to optimise the machine and increase its output. Arguably, user-feedback is useful for tweaking the machine to perform better, and optimally get more users to purchase its output. And outward PR (marketing) also means that more people are aware of your great machine and want the output. Ah, machine-analogies, gotta love them.

Just like the life-cycle-model of a product, which evolves from slow to strong growth, to maturity, and ultimately decline, our machine is very susceptible to tweaking at the early stages, can produce extra output, etc., but ultimately reaches a saturation-point. The same, I believe applies to user-feedback and marketing. The return on investment levels off after a while.

You have the PR, which is the interviews and other kinds of marketing, and there's the user-feedback, which should be restricted to the product-level. And, aside from the life-cycle-model, there is general a limit to the value of both. You don't want a mob disrupting your interviews, no matter how bad they go. You don't want a mob disrupting your business, period, unless you're developing something like a nuclear weapon.

What I'm essentially arguing against is that companies should be 100% social. They should be social enough in order to improve their products and let the people know about them. Should they engage in a two-way conversation? Only if it's directly product-related or your business is bad for the environment (arguably a government-issue), should you engage and customers should vote with their wallets. Note that I'm referring to business-PR here; individuals can blog about whatever they want, if you ask me.

There will always be the "backroom-talk," the social-media people who have opinions on anything, from using Plaxo-scripts to milk Facebook-data, to 17+ ways on how you should (not) run your start-up. And there will always be "Skynet"—the realm of the machines—which have to keep running because social media will not put that food on your table, the farmer will.

This somewhat-cynical article will NOT be mirror-posted on Tech IT Easy tomorrow

Filed under: blogging, branding, business strategy, community, culture, customers, entrepreneurship, ethics, marketing, media, operations, retail, trends, vision

Cooking is ingredients!… it's timing!… it's cleanliness!… it's… … …restraint!

These are just a few of the tips that Gareth Blackstock, chef at Le Chateaux Anglais, and lead character of the British comedy-series "Chef!," delivers to his staff in a kind and gentle manner… not. Even after re-watching this show 10+ years later, I'm still not sure whether Lenny Henry's portrayal of the angry chef is meant to be a realistic, or rather a satiric look at what goes on in these kitchens. The effect it's had on me, in any case, is one of silent terror when I think of kitchens in 2-star restaurants.

These are just a few of the tips that Gareth Blackstock, chef at Le Chateaux Anglais, and lead character of the British comedy-series "Chef!," delivers to his staff in a kind and gentle manner… not. Even after re-watching this show 10+ years later, I'm still not sure whether Lenny Henry's portrayal of the angry chef is meant to be a realistic, or rather a satiric look at what goes on in these kitchens. The effect it's had on me, in any case, is one of silent terror when I think of kitchens in 2-star restaurants.There's no denying that, generally, the world of HoReCa consists of flat hierarchies; there's the boss, either the head-manager and/or the head-chef, followed by some type of administrative class of underlings, and finally those that Gareth Blackstock likes to call

"There's the aristocracy, the upper class, the middle class, working class, dumb animals, waiters, creeping things, head lice, people who eat packet soup, then you.."

If you're thinking of high-tech start-ups in the IT-world, multi-star restaurants are their equivalent in the HoReCa-world. Competitive advantage in technology comes from both products that are differentiated enough from the competition and processes that enable a business to produce these products at a sufficiently low cost and high scale to reap a profit.

In restaurants, this is embodied by the chef, whose training, experience, personality, and, I guess, raw talent, inspire fear in all of those around him, especially the ones that feel his wrath. It is an innovation machine difficult to replicate, comes at a high price and is not for the faint of heart.

Everything else: coming up with a business-plan, talking to investors, setting up the site, buying the materials, hiring the people, getting customers to visit, etc.… seems easy, compared to finding, keeping, and managing a good chef. Because as soon as the chef finds out that he is the one that keeps the ball rolling, he is the vital cog in the machine, he will likely fire you as a boss and replace you with one of those people, generally found under head lice and packet soup.

So there you have it; I don't write about cuisine, same as people generally don't think about starting a business in space-flight. They are both sciences reserved for an elite pioneering-class, one that is fearless and willing to risk the laws of nature in order to succeed.

Filed under: cooking, entertainment, entrepreneurship, horeca, human resources, humour, innovation, management, operations, restaurants, retail, technology

5 links: the obvious one, brand-logic, happy places, e-toys, neuroscience

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 11:02 AM It's Sunday again, and I have a nice big collection of links today: on running a cheap yet effective start-up; on why brands exist; on creating happy places for yourself and employees; on the business of children; and finally on a whole load of neuroscience. The aesthetically pleasing picture of Marilyn links to a particularly disgusting image of a "healthy" burger—my initial choice of illustration. You have been warned.

It's Sunday again, and I have a nice big collection of links today: on running a cheap yet effective start-up; on why brands exist; on creating happy places for yourself and employees; on the business of children; and finally on a whole load of neuroscience. The aesthetically pleasing picture of Marilyn links to a particularly disgusting image of a "healthy" burger—my initial choice of illustration. You have been warned.

Previous link-discussions can be found here.

Link 1: the obvious one - Seriously, unless you actually used this weekend to, eh, have a life, you'll have noticed the firestorm started by Jason Calicanis, continued with Duncan Riley, tempered by Jason Fried, and the final words of wisdom by Micheal Arrington. Crazy, how opinionated these entrepreneurs/bloggers are, right? Yeah, right. A good read if you're (thinking about) running your own business, with like lazy employees and expensive tables.

Link 2: A brief history of brands - well actually a blurb about a book. I like:

"Branding became necessary when large-scale economies started mass-producing commodities such as alcoholic drinks, cosmetics and textiles. Ancient societies not only imposed strict forms of quality control over these commodities, but as today they needed to convey value to the consumer. Wengrow finds that commodities in any complex, large society needs to pass through a "nexus of authenticity.""

Link 3: the architecture of happiness -

"There are three concepts central to the “yoga of the home”…. The first rule is to align your schedule with universal schedules by getting up and going to bed with the sun. “We try to keep lightweight and low furnishings in the north and east — to create an openness — so that we can draw in the healthy early morning sun,” says Cox. Heavier, taller furniture goes in the south and west. Second is bringing nature indoors — plants, natural fibers, no synthetics. “Vastu is the first intentionally green science,” Cox says. And last, vastu asks us to “celebrate who we are and what we love” by surrounding ourselves with things that have meaning. “When someone enters our living room and we’re not in the room yet, we want this guest to get a sense of who we are,” she says. “The room speaks of us.”"I've been thinking about this topic and the general issue of creating happy places for a while. A worthwhile read is also Frank Addante, a serial entrepreneur, on choosing the office-space for his start-up: link 1 and 2.

Link 4: building a toy e-commerce store - since I linked to Lego last time this seemed appropriate. In all seriousness however, I think the subscription-model + children is a cash-cow; kids always want more stuff and have old stuff to get rid off. Applicable not just for toys, but clothing and furniture as well.

Link 5: Some neuroscientific stuff - ignorant shoppers are blissful, though information that stimulates the imagination still works (as do quality-labels as they allow you to charge a premium); body-language works for consumers, in other words an in-store-television-advert or one of those annoyingly friendly taster-people in supermarkets, should cause people to buy more food. A little bird tells me this applies more to the US than the French; 15% of women don't like perfume, which is interesting I think as I'm not a big fan either; and Art-adverts work, enough said. And yes, EurekAlert is my new favourite site.

Filed under: books, branding, Children, design, e-commerce, entertainment, entrepreneurship, food, human resources, Links, management, marketing, neuroscience, real estate, retail, trends

When I first wrote this post this afternoon, it was really long. After cutting it a little it's still really long. Sorry about that.

When I first wrote this post this afternoon, it was really long. After cutting it a little it's still really long. Sorry about that.

A lot of people I know from uni are into this thing called New Business Development (NBD). It makes sense, since it's the title of a course we studied together and it was absolutely the best course I've had in my life. Around 60 hours of hell per week for 2-3 months, but one hell of a ride too.

NBD is a necessary mechanism for when your core-business is stagnating. Let's say you have a good high-volume business, but competition is hammering you with low prices. If you can find a new business opportunity that allows you to make money differently, preferably at high margins, it's a good business opportunity. If it's synergetic with your core-focus, then it's an excellent business opportunity. Three small examples I stumbled across these last few days come to mind.

1. Bookstore + café. Verdict: logical

Buying books is a luxury. They serve no real purpose (unless you want them to) and are generally aimed at price-insensitive people. It is also a fairly slow sale. You are selling information, people are swamped with information, and it takes them time to make a decision. Sometimes… not always. I think time + the amount spent on an item also correlates positively, up to a limit.

That combines well with a café. The luxury-aspect allows you to charge more in cafés as well, meaning higher profit margins. Cafés lead people to relax and spend more time in bookstores, meaning they will likely purchase more books too. Combining the high traffic of price-insensitive consumers together with high profit margins and you have a good business. Also, it's a great way to compete against online-retailers, who are not able to add the atmospheric value.

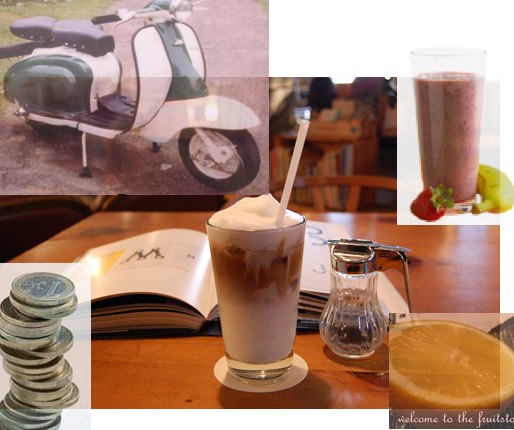

2. Fruit-vendor + fruit-shake stand. Verdict: logical

Fruit is generally a low-margin product. The fruit-vendor in question sells 5 KG of Spanish oranges for €2. You can charge more for fruit-shakes; To the consumer, they taste good, represent health, and require very little in work (all emotional values = higher price-insensitivity). The fruit-retailer sells an orange fruit-shake of 0.5 litres for €2.50. Assuming that's about 1 KG of Spanish oranges, that's quite a lot more profit than €0.40 would give you. But of course there are other considerations.

The fruit-vendor is located right in the centre of Rotterdam on the busiest street. Likely the cost of renting a place is expensive, so is the added cost of producing the shake. The fruit-vendor also competes with a fruit and vegetable market, located a few hundred metres away, and a supermarket, 50 metres away. And his new business competes with other fruit-shake stands. What makes this combination work?

The higher profit margins for convenience-fruit-products, combined with high volume of people passing by is good. It also persuades investors to loan the money for the fruit-shake machinery, which they would probably not do for a low-margin business in a less favourable location. There's a lot of efficiency also; fruit is sourced from the same suppliers, so are packaging-materials, and the retail-space acts as a warehouse. Because fruit is cheap and the retailer has a large selection, he can charge lower prices than the competition and offer more variety. And he enjoys high profit margins even if the volume of fruit-purchases is lower because of the price-competition from the (super-)markets.

3. A eurostore + scooters. Verdict: illogical

This case is a little more complex and contextual. A year ago a eurostore, which is like a dollarstore—a shop offering a great variety of goods at low prices—started offering scooters alongside their regular products. They quickly abandoned the experiment and I have a theory why.

Likely this deal came out of partnership with scooter-retailer/-importer. The eurostore was in a good location with lots of traffic (good for the scooters) and the scooters would give it much higher margins than their regular products. Seems like a win-win.

Consumption of "euro-"goods is different from that of scooters, however. With the first, people expect stuff to break and don't come asking for a warranty. They just buy another. Buying a scooter or anything over a certain amount is very different. People expect extensive information, they may want a test-drive, they certainly want a warranty, and after-sale support.

Since the eurostore is what it is, a store with low margins, this kind of service is out of its realm. It ends up referring customers to the actual scooter-retailer, and very likely the purchase happens there also. Unless you have a contract that specifies this eventuality, gone is the alluring profit-margin. And that, as they say, is that.

Final thoughts

High traffic of goods is a good basis for new business development. It means you have a customer-base to which you can try and sell other products and services, hopefully at a good margin. Location and demographics are important also. Both the book- and the fruit-retailer were well-located and had access to a good demographic, allowing them to sell at high margins and high volume. The eurostore was only well-located. Synergies are vital. For the bookstore it was consumption-pattern and price-insensitivity; for the fruit-vendor it was offering essentially the same product in different packaging; for the eurostore there was little, or rather, none.

Isn't new business development fun? And was my analysis correct?

Filed under: books, branding, business strategy, café, coffee, community, culture, customers, entrepreneurship, food, geography, Health, horeca, logistics, marketing, new business development, operations, real estate, retail

When I started this blog as an experiment, I purposefully kept it vague, while maintaining a fairly clear industry-focus. However, taking a value-chain view of food & retail only gives you so much. It allows you to identify tensions and possible opportunities, but unless you want to be a consultant regarding value-chain issues or are the strategist within a business, it doesn't really bring you all that much.

When I started this blog as an experiment, I purposefully kept it vague, while maintaining a fairly clear industry-focus. However, taking a value-chain view of food & retail only gives you so much. It allows you to identify tensions and possible opportunities, but unless you want to be a consultant regarding value-chain issues or are the strategist within a business, it doesn't really bring you all that much.

Where the imagination really kicks in—and you need that to think of new business ideas—is when you start matching you— the individual or groups of individuals with a particular skill- and experience-set—with a particular opportunity that you can feel both passionate about, and confident that your skills & resources are sufficient to add value to it.

Blogging about FnR allowed me to look at segments in the industry, such as:

- farming

- supermarkets

- franchises

- online-retailers

- electronics retailers

- coffee-shops

- restaurants

- cinemas

- furniture-stores

- and fitness-studios

- fast-moving consumer-goods

- coffee

- beer

- private labels

- organic food

- and media

However, starting or working in a business is of course more than writing about it. It's the process of building up a vision, gathering up resources to execute it, and executing it. I was reminded of how powerful such a vision can be just last night when I was evaluating a business-idea and what it would take to execute it (I ended up dismissing it for now).

And of course, starting a business is not the same as running a business, the latter of which can be defined as a sustainable* process of making money (*: not in the environmentally-friendly sense of the word). So many stages to go still.

Will this have consequences for this blog? In the short-term, the next few months, probably not much. I'll still be looking at more industry-segments, product-areas, and business-issues. Ultimately though, I will have to focus on one particular industry-segment and one or a set of related product-areas. Of course, when that happens, I'll continue to share my thoughts here, as that is my not-so-secret way to build mindshare (insert: evil laugh).

Take care,

V.

Filed under: About, business strategy, community, entrepreneurship, horeca, retail, self-development, trends, vision

As some readers may know, I've both read and commented on Malcolm Gladwell's Tipping Point, and found it an interesting book to think about the nature of communities and how certain individuals or groups of them are more influential in passing on ideas than others. That said, while I believe that such "influencers" exist, also from personal experience, I know fairly little about the science of it.

Similarly, Duncan Watts a research scientist at Columbia, working at Yahoo, questioned that principle, asserting that news travels fast, through whatever type of individual. I have no doubt that Yahoo has amassed vast amount of data on what source of del.icio.us bookmarks receive the most clicks, etc., and that the nature of the internet allows even the lowest of the lowest content-provider or -mediator (e.g. yours truly) to lead people to news.

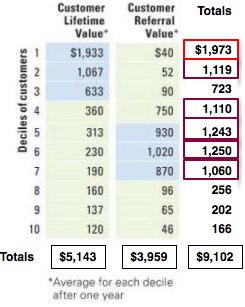

A recent HBR-article gave me some insight into the complexities for companies to measure the value of such referential actions, something they call Customer Referral Value (CRV). It is calculated by estimating the number of successful referrals made by a customer, but differentiating between new customers that came because of his/her referral, and those that would have come anyway. It's a fairly complex formula and requires some extensive market-research, but you can find a good overview in the HBR-article.

This is opposed to a customer's lifetime value (CLV), the traditional way of measuring the value of customers, which looks at the amount that the customer's purchases contribute to the companies operating margin, less the marketing costs to him or her, and projected over a certain period of time.

Using this methodology, the authors of the article measured both the CLV and the CRV of 9,900 customers at a telecom-company and came up with following results:

I added the totals myself, because I thought those would also be interesting. What you can see here is that those with the highest CLV also presented the highest total value to the business, though CRV added considerable value also. What's also interesting is how these are distributed. The high value shoppers added relatively little in referential value, and only in the medium-levels do we see a high amount of CRV.

Through three one-year marketing-campaigns aimed at the high shoppers with low referential value, the medium CLVs with high CRVs, and the low of both, the company tried to stimulate the customers with lower values in either segment to do more, either by spending more or by referring more. The result was a 15.4 return on investment on the marketing-campaign, meaning that for each dollar spent on marketing to customers, $15.4 was gained in revenue.

Clearly, I could say more about how the authors went about it to make these kinds of gains in both CLV and CRV, however that's why this nice article was written about it and I encourage people to check it out if they're interested.

Are there implications for the Gladwell vs. Watts fight? In my opinion, either could be right. What Gladwell has merely done is open our eyes a little towards this whole viral marketing-thing, though certainly some companies were already busy with it. And what Watts is pointing out is that there is great value in building on top of existing networks, something I'm sure the telecom-company benefited from also. The greater lesson here is to look beyond the CLV of a customer, though that already brings a high value to companies, and focus on methods of stimulating word of mouth in innovative ways. How that is achieved depends on the type of business and the networks that it can use to communicate with its customers. Certainly, Milner cheese, which I wrote about a few weeks ago, offers one possible answer. Update: and so does the recent marketing-move by Etsy on Twitter.

This article is mirror-posted on Tech IT Easy.

Last weekend, the Dutch financial Times, FD.nl, had an interesting part-article / part-diary of Henk van der Doelen, owner of a chain of ca. 30 drugstores in the Netherlands. Originally part of a franchise called DA (2nd largest in the Netherlands, afaik), he and several people decided to split because of restrictive conditions. I've followed this story for a while because I'm interested in franchising, and because drugstores are big business in the Netherlands (market-size: ca. €3,5 billion), probably due to its trading history in spices and herbs.

His company, Drogisterij-parfumerie, was founded in 1970, has 270 employees, 29 branches, and an annual revenue of €23 million.

The business also employes a franchise-formula, called 'Pour Vous' (Dutch link), which has existed since 1975 as a soft franchise. It asks a monthly marketing-fee of €250 and / or (this part is unclear) €7000 per year for commercial and marketing-related activities. Total innital investment to join the formula is estimated at €300.000.

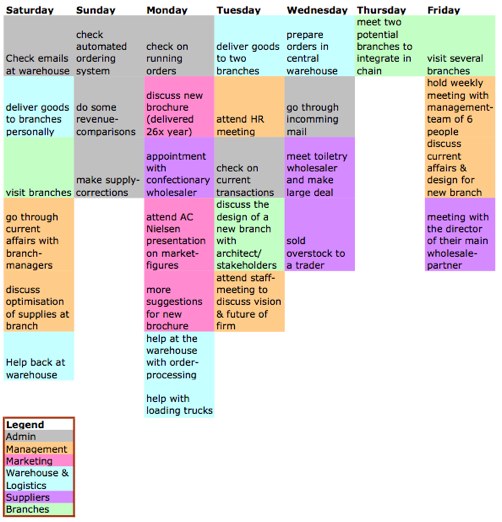

I created the colour-coded picture below out of curiosity. How exactly does a retail-chain owner divide his time? Naturally, one week's activity should not be generalised across greater periods or different businesses, and I probably mislabelled some activities. But you can let me know that in the comments. ;-)

What is interesting is that there is a fairly even division of activities, apart from maybe marketing. From the article, I did get the sense that he was more focussed on warehouse-actitivities, also living close to the central warehouse, but he pretty much kept his finger in all the relevant pies for running a business of this sort.

What is also interesting is that he essentially plucked out a number of franchisee-branches out of DA's franchise-network and created his own. In the sense of whether franchising is entrepreneurship or not, I do think that this again confirms that the options remain wide open. This story also sheds a light on what can happen if a franchiser's policies are too restrictive for franchisees.

From my understanding, DA has been making moves towards a more integrated strategy, which did not sit well with many franchisees. Apart from the ca. 30 branches that Drogisterij-parfumerie took with it, another 40 left to join D.I.O. (4% market-share). This still leaves DA fairly strong, with 452 branches and 15% market-share, behind the number 1 in the Dutch market: A.S. Watson (Kruidvat, Trekpleister, and ICI Paris XL) with 877 branches and 40% market-share.

Filed under: business strategy, entrepreneurship, Franchising, logistics, management, operations, retail, suppliers, supply chain managment

Let's face it, even with nature knocking on our door, some accountant will still ask what this whole thing is going to cost. Science, facts, morality… it's not enough. I compare it to smoking; even though everyone knows smoking kills, it took pressure—social, governmental, commercial—for people to quit. And the same applies to businesses going green.

Let's face it, even with nature knocking on our door, some accountant will still ask what this whole thing is going to cost. Science, facts, morality… it's not enough. I compare it to smoking; even though everyone knows smoking kills, it took pressure—social, governmental, commercial—for people to quit. And the same applies to businesses going green.

Without further ado, here's five pressures that make the business-case for companies to change.

1. Governmental pressure - let's ignore for a fact that government is the one keeping its finger on the pulse of scientific research, social, business, and technological trends. But what is hard to ignore is that the government is actively pushing businesses to change, either by punishing the wrong-doers, by subsidising clean practices and technologies, or by providing new infrastructures around these new rules, allowing for businesses to dispose of their waste in better ways and use alternative, cleaner energy-sources.

2. Consumer pressure - like with smoking, not all consumers have been following the new green "religion" quite as passionately. That said, there are the early adopters, the geeks, the pressure-groups, that are insisting on businesses changing their ways. And those businesses are themselves customers to their suppliers and are doing the same thing to them.

3. Business climate pressure - apart from the above, two things will strongly pressure businesses to change: costs and competition. The rising cost of fuel, electricity, and water, etc., as well as the cost of disposing their waste, is a good incentive to implement technologies that help conserve energy and produce less waste. Similarly, as competition will do the same, businesses are forced to respond.

4. Knowledge-carriers - with the amount of scientific research being produced everyday, it was only a matter of time before methodologies would be developed to help businesses become greener. Since this is still a specialised activity, both commercial parties (consultants) and governmental institutions are there to advise companies on how to change.

5. New technologies - new inventions are constantly being brought to the market, that help businesses conserve energy or get it from alternative sources. Think: technology to monitor and regulate energy-use, water-conserving toilets, more efficient lights, green roofs, etc.

Anything I missed?

In a way, you can't blame businesses for resisting. There have been lot's of change-initiatives these last decades—from ERP to joint ventures—which have produced questionable, if not disastrous results. For change to happen, it must be driven by strategy first, because doing business is like doing war. There is a high price for failure and no one will be congratulating the loser.

But what is certain, is that eventually there will be no more choice. Those that are slow to react will do so at the cost of an unsympathetic government, of the competition racing ahead, and of customers dropping their support.

This article is mirror-posted on tech IT easy, where there's also an interesting discussion going on. Why do people end up going green?

Filed under: business strategy, community, culture, customers, eco-trends, ethics, Globalisation, green, innovation, Legalese, operations, Politics, retail, subsidies, trends

5 links - sense of smell, false green ads, farming boom, Lego, fun e-shopping

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 10:49 AM Time for those Sunday-links again. Today, I'll discuss the cocktail that is smell and how some things just don't mix; how green is not all it's cut out to be; a possible shift of power from retail to farming (or not); how lego came to be and where it is going; and how to sell me online shopping.

Time for those Sunday-links again. Today, I'll discuss the cocktail that is smell and how some things just don't mix; how green is not all it's cut out to be; a possible shift of power from retail to farming (or not); how lego came to be and where it is going; and how to sell me online shopping.

Previous link-discussions can be found here and my bookmarks here.

Link 1: Starbucks Admits Sensory Mistake - These are the kinds of stories that make me I like the NeuroscienceMarketing-blog. If you follow the science-section of the Economist, you'll know that neuroscience is a big deal anyway. In any case, this story is about how Starbucks designs atmosphere, largely influenced by smells. Apparently, smell of heating egg and cheese sandwiches doesn't mix well with the coffee aroma.

Link 2: False 'Green' Ads Draw Global Scrutiny - Two problems linked to green adverts these days, I think. One is that consumers are growing tired of it. And two is that, as this story shows, just because companies say they are, doesn't mean they are. I like the Norwegian approach to this. They ban green adverts by products that cause more problems, no matter how innovative they are (about hiding it).

Link 3: Farmers Wonder if Boom In Grain Prices Is a Bubble That food-prices are rising is an inescapable fact. But it also presents an interesting shift in the status quo. In the food-chain of the grocery-business, farmers are pretty much at the bottom. Now, even though their own costs are increasing also, they can charge more on top of it and decrease retailers' margins. Time will tell if this is something that will be acceptable for a long time. Certain signals very much suggest to me that farmers may be in the right position to cut out the middle-man and become retailers themselves.

Link 4: The Making of…a LEGO - I'm still a kid at heart, so I love anything to do with games and toys. My parents never bought me much lego as a child, which I regret as I hear it breeds geniuses. In essentially two pages, the article describes how lego came to be, what makes it so perfect, and what the company's strategy is. I was always impressed with the brand-extensions they did with the games, the robots, and the theme-park. A company to follow.

Link 5: Online shopping at Hema.nl - I've linked to this on twitter before, but it brought another smile to my face watching it again. Just when I think that online-shopping has no future, innovative uses of technology surprise me again.

Filed under: branding, business strategy, coffee, culture, design, e-commerce, eco-trends, entertainment, ethics, farming, food, green, horeca, humour, innovation, Links, marketing, media, retail, starbucks, trends

The role of the internet for the retail of *physical* goods.

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 9:01 PMOne of the stories, I covered last week in my links, uncovered an interesting statistic. Only about 3% of retail sales in the US happens online. I don't think these stats are at all coincidental. While I see a bright future ahead for the online retail of media-products, I find that what the internet cannot provide, is the "closeness," that is sometimes needed for evaluating certain types of goods, like food and clothing. I have commented on this before, implicitly, with a post on the web as a third place, and about the lack of cohesion that Facebook provides.

At the same time, as The New Yorker story reports, what the internet has changed is how we shop; it is much easier to research and comparison-shop than it was before the internet-days. A survey by Accenture found that ca. 66% of those surveyed compared products online, and another study showed that the internet played a significant role with ca. 75% of electronics purchases.

IInnovate has an interesting podcast interview with Scott Dunlap, CEO of NearbyNow, which has come up with an interesting way to exploit the informational advantages of the internet and mash that with the qualities of physical shopping. Following short video shows how their service works:

Clearly technology has evolved a lot in the last few years, making this possible. NearbyNow works via the web and via mobile. I'm not sure if they are using any location-tracking & matching services, but certainly they are heading in that direction. On the retailers' side, there is plenty of technology that makes this possible also. Electronic inventory and point of sale systems allow both for the checking of stock-levels and for consumers to reserve items to be picked up and tried on at a later date.

One issue that entered my mind, is that of efficiency. The way NearbyNow operates is through malls in the US, most of which are, as I found out, owned by 6 major companies across the nation. US's scale-economies win again! In Europe, the situation appears a little different. Culturally, linguistically, technologically, and legally, it is a much more fragmented market, with far fewer malls also, and that may make it difficult for a unified service like this to operate as efficiently as it would in the US.

There is also the issue of too much transparency, which is worrying to some retailers, and addressed in the podcast-interview. But what does seem certain is that this is exactly the type of service that consumers value, and as such one that any consumer-centric business should encourage.

Will a service like this ever replace shopping in its entirety? No, I'm essentially betting my future that there are plenty of qualities *real* environments will continue to offer over virtual ones. But there is no reason, none at all, to try to integrate the good qualities that the web does possess—information at your fingertips—as elegantly and effectively as possible into those experiences.

Filed under: business strategy, customers, e-commerce, entrepreneurship, Europe, geography, innovation, logistics, marketing, operations, retail, supply chain managment, technology, tools, trends, USA

The

The