One of the things I do on this blog is deciding on the potential of industry-segments, ranging from farming to coffee-shops, and from grocery to other types of retail. On Tech IT Easy I've previously expressed my scepticism at media (in which I include text, art, audio, video, and gaming), especially in terms of business-models, which I think that segment lacks.

One of the things I do on this blog is deciding on the potential of industry-segments, ranging from farming to coffee-shops, and from grocery to other types of retail. On Tech IT Easy I've previously expressed my scepticism at media (in which I include text, art, audio, video, and gaming), especially in terms of business-models, which I think that segment lacks.

Equally so, I see fairly little space for it in the physical retail segment, simply because it is so much more convenient to purchase and consume it via digital means. The PC (and other tech-gadgets) have essentially become the hub for all things media, and creating barriers to that experience just leads consumers to pursue more convenient ways of experiencing that media. That search for convenience is something that I've also approached in a previous post on this blog.

Let's look at some media-types and how they are being sold online.

For Video - there's iTunes, consoles, and set-top boxes that are controlled by media-producers. In any case, the power-differentials between producers and intermediaries is very unbalanced and it isn't a nice segment to enter as a retailer. Also, let's not forget the free alternatives: YouTube et. al and piracy.

For Audio - again iTunes, Rhapsody, and Amazon MP3 Store, but also smaller digital store for independent artists, like CD-Baby (which operates through iTunes also). Let us again not forget piracy and the fact that much of music is being produced through digital means and it makes sense to organise distribution that way also.

For text - there's again online outlets like Amazon for eBooks (Kindle) and Zinio for magazines. And let's not forget that 99% of text-based media is viewable for free online. Still, admittedly, electronic devices for consumption are not yet able to compete with paper-based methods, at least where price is concerned. Also Audible should not be forgotten as a source for audio-books, recently bought up by Amazon and partially distributed through iTunes again.

For Gaming - I'm not too familiar with the online market for this one. Even so, there's Steam, a digital distribution system by Valve, a platform which they recently opened up for use by other game-publishers. There's also plenty of smaller games being distributed through Xbox-live, the future Playstation Home, and of course the internet.

Finally, Art - here the situation is more complex, while on the other hand being relatively simple. It is complex for artists like my mother, who paints, and conducts business on a personal level by interacting with her customers. On the other hand, there's photography and digital art, arguably the evolution of traditional art, which is easy (for some) to produce digitally and distribute online. I suppose every industry has that friction between the traditional way of doing things and "the new way."

All in all, I don't see media as a big cash-cow for physical retail. I like to think that, because production and distribution becomes cheaper, that its cost will eventually fall to a very low price, allowing for it to be included as an added-value component in the service-proposition of physical retail-outlets (to which I also include restaurants, etc.). I also like to think that creating environments that make the consumption of media a comfortable process (e.g. cinemas) also has some potential.

But my outlook for selling media as a product, something that could easily be sold digitally, remains bleak. Please let me know if there are arguments against my point of view, as I'm here to learn.

Filed under: Amazon, Apple, books, culture, e-commerce, entertainment, innovation, media, music, retail, technology, trends, vision

Dear readers,

I'll be taking a few days to a few weeks off to reflect on my current state and activities, my goals and the steps needed to reach them. I'll likely post a few thoughts about this on Tech IT Easy in the near future, as that seems more suited for that somehow.

Until then, my links are being still updated and I'll discuss some of them this weekend again. At the end of this month, I'll also wrap-up what I've covered in February 2008.

Until then, take care,

Vincent

Premise of this post: Jeremy wrote a nice post today about the boons of starting young and I spent some time this morning advising my sister on writing a business-plan.

A picture says more than a 1000 words

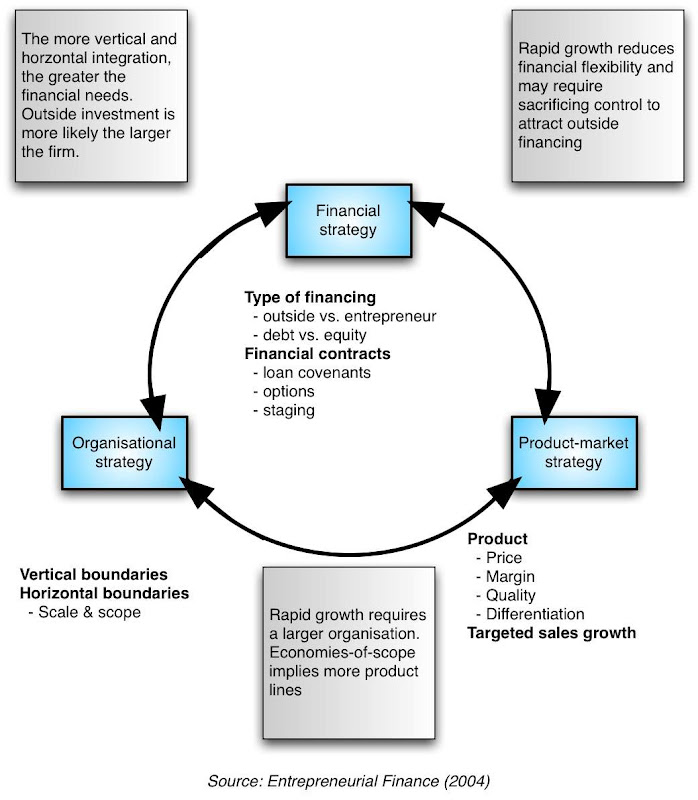

Strategy consists of three components, the financial, the product-market, and the organisational. All are interdependent and when they are in harmony, the chances of success are greatest.

For example, a larger organisation, which is a consequence of a more complicated product-market strategy, will also increase the need for financing, very likely the external kind.

Essentially you have to decide:

- What type of product(s) do you want to launch? What kind of market are you targeting?

- Do you want to be big (less control) or small (more control)?

- Do you feel comfortable with giving away shares of your business to investors?

I created the picture myself, but it was inspired by a graph in the book "Entrepreneurial Finance".

Filed under: business strategy, entrepreneurship, finance, Research, retail

"The Disney Way" oh, how I hate thee, as a book, so far (UPDATED!)

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 9:27 AMUPDATE: After skimming through the book, I did manage to find some more informative chapters on how to structure creative enterprises. So, I'll raise my score of the book to 5/10, and will update when there's more to say. I was actually not planning to write anything too bookish this week, having championed their status for more than a few days last week. I just want to say that, ever since starting reading TDW, I found myself growing more and more uncomfortable for a few reasons.

I was actually not planning to write anything too bookish this week, having championed their status for more than a few days last week. I just want to say that, ever since starting reading TDW, I found myself growing more and more uncomfortable for a few reasons.

First of all, the credo that the book is trying to sell to me is "Dream, believe, dare, do." Yes, I remembered it without checking the book. DBDD is such a simple system, meant to emulate Walt Disney & Co's way of thinking, that pretty much any idiot can remember it.

And that is how I feel like I'm being treated. Like an idiot, who can't remember more than four words.

The book is split up into parts, representing each of the four "magic words." I started on 'Dream,' expecting to find practical story-boarding tips. I'm not yet done, so maybe at the end, but all I've been reading was about companies that the authors consulted, which had "big problems" and now are "a leader in their industry." There is very little, except for between the lines, which I can use as a case-study for me to think that I can replicate this in my own company.

The method most mentioned, is to create a "Dream Resort" (always capitalised, because it's the authors' business). If you go to a Dream Resort, all your creative barriers will fall away, the magic will happen. Believe it! Well, until I see something that justifies spending 1000s of dollars on consultants, or how I can replicate some methods on my own, I don't believe it.

The only instructions I remember reading so far, was a pseudo-sociological experiment with monkeys. Apparently, if you put 99 monkeys on a beach with sandy fruits, one monkey will work out how to wash his fruit in the sea and make it taste better, and eventually the other monkeys will learn from him. And, I paraphrase: "That's how companies learn too." We are all monkeys!

Somewhat ironic, the authors mention several characteristics that people don't like about how big companies are managed, such as arrogance and not including employees in solving problems. I would like to add treating people condescendingly to that list.

The lack of dreams, you could argue, is a big-company problem, which is another incompatibility-issue with some readers like me. There is no creative barrier, really, what is needed is a framework to build a business around it.

Also, small companies are flatter, there are less structural problems preventing the spread of ideas, it is actually a survival mechanism that everyone takes part in steering/fixing the machine that is a start-up.

Anyway, I decided to give this book until the end of the 'Dreams' chapter. If I don't get clear-cut language by then, I'll skim and throw it away.

And I still can't believe that I'm being advertised to buy services in a book that I already bought. An end-of-book brochure is fine, but so far it's very much over the top.

Reviewer's current grade: 3/10 and I'm being generous.

Filed under: books, Disney, entertainment, operations, Research, retail

5 links—retail-saturation, RFID's costs, elements of fun, tricking shoppers, & home-cinemas

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 10:41 AMIt is time for those links again! This time, we'll be discussing the economics of Apple's physical stores, how Walmart is enforcing RFID, how retailers are trying to trick people to buy more expensive things, how people perceive fun in games, and 10 ultra-geeky home-cinemas.

As usual, my bookmarks can be found here, and the previously covered links, here. Enjoy!

Link 1: Why is Apple saturating (US) cities with retail stores? is a question that Choire Sicha asks on Kottke.org, and lead me to this profit & cost breakdown of Apple's retail stores at Seeking Alpha (see pic below). It does appear it's all about the money, though hard it remains to read Apple's mind 100%. In related news, OObject lists all the items needed to build an Apple store.

Link 2: Is RFID economically feasible? I'm planning to dedicate at least 1-2 posts on RFID on this blog in the future, as I've essentially been following its development since the early coverage on Slashdot. This story on InformationWeek discusses the pressure that Walmart, certainly the biggest champion for RFID in the retail-arena, is putting on its suppliers to finally add RFID into their logistics-chain. As far as I remember, the latter have been complaining about the unfair balance of cost that RFID causes, shifting most of them onto suppliers. I assume, however, that these chips and pallets are reusable.

Link 3: What makes games fun? Lightspeed Venture Partners has an interesting blog, which mostly discusses the business and principles behind digital games. I follow it because games are fun, and if you can understand the source-code of fun, you can replicate it elsewhere. In that spirit, then, it links to an interesting white paper trying to map out what exactly goes on in gamers' heads while playing games. Part 1 is also very much worth a read.

Link 4: A buyer's christmas? The New Yorker digs into consumers' buying behaviour. Interesting is, that people use the net most often to find info, not to buy, but can use that info inside stores (we'll still need ubiquitous internet for it to be shoppers' utopia, however). Equally interesting is, that if a store has two microwaves, consumers will usually buy the cheaper one. With three products, however, they will usually by the mid-priced one. There's still room for trickery, I guess…

Link 5: 10 stunning ultra-geeky home cinemas. In the spirit of my previous post on cinemas & luxury, I thought that this link would be fitting. The Star Trek-themed one is a little too geeky for me, but the Titanic one (no. 6) looks awesome. I'm still doubtful about whether it's about the design or about the movie, but I can't deny that people put a lot of work into designing these.

Filed under: Apple, business strategy, cinema, customers, design, entertainment, innovation, Links, logistics, retail, RFID, suppliers, supply chain managment, technology, trends, Walmart

If you follow my blogging-history, you may have noticed that I write about books… a lot! There are several reasons for this. One is certainly that I am a bookworm—I enjoy reading books, learning new things, and whenever I enter a bookstore, I go into a trance and start studying books to buy now or in the future. Case in point: I wasn't planning it, but I bought two more today! Talk about impulse-buy… More on those in a sec…

If you follow my blogging-history, you may have noticed that I write about books… a lot! There are several reasons for this. One is certainly that I am a bookworm—I enjoy reading books, learning new things, and whenever I enter a bookstore, I go into a trance and start studying books to buy now or in the future. Case in point: I wasn't planning it, but I bought two more today! Talk about impulse-buy… More on those in a sec…

The other reason is more complicated. I actually think that books translate better to blogging than much of real life. This clearly differs from blogger to blogger. You won't find Robert Scoble blogging about books much, nor Fred Wilson, both of whom blog on more daily issues (Scoble is also a media-guy). Both John Gruber and Jason Kottke do cover books, but often base their writings on articles and other shorter readings.

For myself, it is different and I can give several examples of this. One, I was a pretty regular blogger until about a year and a half ago, when I started on a project of researching venture capital in the Netherlands. Not only was it a time-intensive process, but I was constantly questioning myself as to whether my blogging was ethical or not. There were certain topics reigning in my life, relating to that company, which i could just not disclose. A similar thing happened before that, when I worked at a high-tech start-up, and most recently, while completing my thesis.

There are several blogging friends I could mention (F., J., C., & M.), where you notice this same phenomenon.

Books instead, as well as articles, offer a foundation to build upon. One, they are public, which dismisses any confidentiality issues. Two, if they are well-written, they communicate core-ideas well, and you can add to that with your own knowledge. The complication with reading is of course, similar to writing, finding the time to do so. I think I found a doable system, by reading just before sleep, but I don't know how that will hold up in future projects.

The way I choose books (and articles)

As I look back at my short life, I find that I've evolved in the choices of books I made, and most recently after engaging on this trajectory—the food & retail blog and the underlying purpose that serves. While before, my choice of business-books was somewhat restrained to general management, strategy, and entrepreneurship books, I now choose books purposefully that fill a gap in my knowledge and focussed on business-issues in this industry.

Some examples

I choose the McDonalds (coverage here & here) and Starbucks books (here, here & here), because they seemed like a good venue-point from which to understand how food-businesses work. My interest has always been towards chains of businesses, not individual ones, so that was also a bonus. Similarly, the IKEA-book (here) offered insights into retail, and the eBay-book (here), while less relevant, into starting a business and running a community.

The Disney-book (here), which I'm currently reading, gives me insights into building a framework around the soft discipline of entertainment, story-telling, etc. It is very relevant to my earlier post today on cinemas, which is clearly a raw perspective, but one I hope I can refine, as entertainment is a core-value I have.

The two books, I've chosen today, are on two diverse, yet, to me, relevant subjects. "Managers as mentors" is about what the title suggests. The reason I chose it, is because I'm not a fan of the traditional perception of management. I find it a hard world. The way I relate to people is through learning and teaching. I've raised my brother since I was 11, as my parents were often away from home, and find it very rewarding to see him become an adult. I have a similar relationship towards people, where I like to turn them into more than they imagine themselves to be. So this book seemed right. That is not to say, that I have any problem with firing people that I don't feel have potential. ;-)

The second book is even more interesting to me, it's called "the growth strategies of hotel chains - best business practices by leading companies." It's very strategy-orientated, covering principles of diversification vs. specialisation, vertical/horizontal/diagonal integration, m&a's, franchising vs. ownership, branding & globalisation, and US vs. European differences, as well as examples of said leading chains at the end of each chapter. Exactly up my alley! Needless to say, I will read it after the Disney book!

So what about you?

Now, a discussion is only valuable if more people take part. So please, if you have an opinion on this, or on a better research-methodology for blogs, let me know in the comments!

The picture is courtesy of brandtarot.com

Filed under: books, business strategy, career, entrepreneurship, ethics, interlude, management, Research, retail, self-development, vision

I'm writing today's post mostly as a way to relax me. I've been in a bit of a panic these last few days because my main machine, my trustworthy mac, is giving me kernel panics and I'm in the middle of a project. It's not a nice feeling, and any repairs, I've been informed, are bound to take 10 days. So, blogging to relax, yes, but don't expect regular ones, especially considering this machine can "explode" at any time. NYTimes recently wrote about a strategy employed by US cinemas to draw in more people. I quote:

NYTimes recently wrote about a strategy employed by US cinemas to draw in more people. I quote:

"Reserved seating, plush rocking chairs and made-to-order food make Mr. Redford’s Sundance Kabuki theater feel more like a restaurant than a traditional cinema. It also has a 50-foot-high lobby with live bamboo, a glass atrium and reclaimed wood walls. Here, a night at the movies is less about enduring the hordes at the mall and more about feeling pampered."According to the article, big US-chains are building such upscale cinemas to draw people back into the experience.

While I am a big fan of the cinema-experience and actually worked at exactly such a venue, years ago, as a cocktail-mixing barkeeper, I think there are several reasons why such a strategy won't work.

The nature of movie-viewing (1): regardless of how luxurious a place like that is, you'll still have to sit in a dark room and won't actively notice the luxury or people around you, except for before and after the movie. The reason why people like dining in luxury-restaurants is because of the luxury, yes, but also because you share it with a group of people. In cinemas, luxury is not an emotional draw.

The nature of cinemas: cinemas are still very much in a mind-frame of providing experience of the masses. That manifests itself in a McDonalds' mentality of serving guests standardised services, having a lot of seat-rotation, cleaning big rooms (badly) in less than 10 mins, etc. It's a lot of little things, but they add up to a reputation for mediocrity, and people really just come to view the movie and be with their friends.

The nature of movie-viewing (2): YouTube, the internet, modern lifestyles, etc. have created different viewing-patterns, and there is a much greater focus towards viewing media in bursts. I think that the cinema-industry thinks that it is competing with some kind of emulated experience at home, but I don't think that's generally the case. So what are cinemas competing with and should they compete with it?

Luxury is not mass: Cinemas need masses of people coming in, and luxury cinemas actually only aim to address the (imagined!) needs of a few. In my opinion, it is not a customer-focussed strategy, and is for that reason alone bound to fail.

What should cinemas do?

Now, I'm not all against a certain level of luxury. I like comfortable seats as much as the next guy and I'd love a good cocktail every once in a while. But I think standards should be upgraded throughout the cinema, all the way down to the lowest seats, and that everyone should have the option to get a cocktail (if they have the budget).

There's two main selling-points for cinemas, I think, and those are timing and technology. They are still the first to air a film (ignoring piracy), which will hopefully not change. So, for blockbusters, cinemas reign is pretty much guaranteed.

Apart from blockbusters, there's something special about seeing indie movies in cinemas, which I include into timing. I'll never forget watching "Howl's moving castle" in the cinema, it was a magical experience, one that I could never have at home.

As far as technology is concerned, admittedly we are in an age where big screens and high-def visuals and sounds are becoming commoditised, though no one is as yet planning to install a 50 ft. screen in their house, afaik. I do think that cinema-technolgy should be upgraded, all the way to the point of the IMAX-experience.

Admittedly, there are some problems with 3D-tech. It increases the cost of producing a film and won't translate well to home-viewing (I think). But my point is that cinemas should keep differentiating themselves technologically.

People is a third selling-point, though I think that unless you like going with 8+ people to the cinema, you will be able to emulate that at home.

As far as luxury is concerned, again the basics should be present, and cinemas have to make money, but cinemas would become a lot more popular if they kept the price of seats down, increased the quality of service, and charged what they charged for luxuries. The one thing that I can't stress enough is staying a leader in technology (video & audio) as that is truly where the emotional draw for cinemas comes from.

But maybe I'm wrong!? Feel free to let me know in the comments.

Filed under: branding, business strategy, catering, cinema, community, customers, design, entertainment, innovation, marketing, media, new business development, operations, real estate, retail, technology, trends

Just some finishing up on the IKEA-book. Following graph describes the structure of IKEA's business, as far as I understand it.

1: Stores - The way the company expands horizontally, is through a tightly controlled franchising system. This both saves costs and minimises international risks.

2: Sales & service - the company is tightly integrates its sales- and service-operations with customers, the latter taking over 80% of the work (and loving it). Huge cost-savings, also benefiting customers.

3: Supply, manufacturing, design - The company is equally well-integrated back up the value chain, with suppliers, manufacturing, and design, and has—since the 90s—been expanding its operations in that direction. Some cost-savings by introducing savings up the logistics-chain, and more flexibility in manufacturing.

4: Management structure - non-public virtual entity that licenses the IKEA brand and is able to offset international tax-differences by being located in Belgium/the Netherlands and changing the terms of licensing-agreement as needed.

You can draw your own conclusions from that, together with what I've written before.

Things that stuck out from the book included:

- Ingvar Kamprad, the founder, who has both a trader's mentality and is at the same time a community-person;

- Sweden, IKEA's country of origin, whose restrictive tax policies actually resulted in pushing the business to become a global company;

- IKEA's cost-philosophy, which is very frugal and part of the company-culture, and also transmitted to the supply side and to customers. Some problems retaining top-employees as wages are not competitive;

- Its franchising-system, which somewhat surprised me, can be explained by the scientific way in which IKEA's operations has been built up. The more rational, the "easier" (a relative term) to replicate. It's also in line with the business's rapid global expansion and its drive to push down costs;

- It's a private company, which makes it less visible and (relatively) less accountable to the public.

- Its vertical integration with suppliers and customers, enabling it to quickly respond to new trends and problems, as well as introduce higher cost-savings than its competition.

P.S. I'll be taking a few days off, to recharge some creative energy.

Filed under: business strategy, community, culture, customers, Franchising, Globalisation, human resources, Ikea, logistics, management, operations, Research, retail, suppliers, supply chain managment

I'm glad to get this out of my life. It is probably the last bit of procrastination left over from the period spent writing my thesis. Following is a continuation of my coverage of IKEA's growth as a business, which I began, in a wordy fashion, by looking at the Scandinavian years. I decided to shorten that somewhat, as really the book (if you can read it) already does a great job of describing IKEA, though my version is perhaps easier to digest.

I'm glad to get this out of my life. It is probably the last bit of procrastination left over from the period spent writing my thesis. Following is a continuation of my coverage of IKEA's growth as a business, which I began, in a wordy fashion, by looking at the Scandinavian years. I decided to shorten that somewhat, as really the book (if you can read it) already does a great job of describing IKEA, though my version is perhaps easier to digest.

1961 - Already when Ingvar Kamprad started trading, he had formed relationships with suppliers from abroad. He employed this strategy also when he launched IKEA, forming relationships with Polish and other Eastern European suppliers, which gave him a drastic price-advantage over his competitors.

1973 ca. - After the incubation-time in Scandinavia, Switzerland was the first country, that IKEA expanded too. Reasons included its neutrality, a healthy economy, low taxes, and a greater entrepreneurial spirit.

1973 ca. - When the Kamprad family left Sweden, they founded several foundations in the Netherlands, Switserland, Panama, and the Dutch Antilles.

1974 onwards - Expansion in Germany, Munich (one of the wealthiest cities in DE). The store was a great success, and Germany is still a pillar of profitability for IKEA today.

1975 - first stores opened in Australia, Honk-kong, and Canada, through franchising. In 1980, IKEA took over the Canada-chains, as those were not being run well.

1978 - First store in the Netherlands. It did not go well at all, due to a lagging marketing-campaign. Only in 1982 onwards did IKEA book successes with the Dutch. 1994 started a huge boom of expansions in the Netherlands (more detail was provided about Dutch branches, because the book was Dutch). Belgium also saw stores after 1978.

1982 - IKEA set up Stichting INGKA Foundation in the Netherlands, which was Kamprad's way of keeping IKEA for IKEA instead of having to give it away after he died. It was in charge of IKEA from then on.

1983-4 - stores in Gran Granaria, Tenerife, and Saudi-Arabia.

1984 - IKEA starts "IKEA Family" loyalty program for customers and also introduces its first luxury furniture product-lines.

1985 - first store in USA and kept expanding. Famously (I read at least 1 case-study about it) there was some teething-trouble at the beginning and it took a while for IKEA to find the correct formula for the US market.

1986 - 60-year old Kamprad steps back as CEO and gives reigns away to 35-year old Anders Moberg.

1989 - the fall of the Berlin wall. The roughly 500 suppliers that IKEA had been working with in the Eastern block, suddenly found their economic situation drastically change and prices started to go up. Out of loyalty, IKEA vowed to pay up to 40% of the price-increases for its Polish partners.

1991 - the Eastern European crisis lead to a strategy-change. IKEA became a producer of furniture. Due to its long-lasting relationship and involvement with suppliers, it possessed the necessary know-how, and becoming a producer would also have positive effects on its flexibility. IKEA could focus on Just-in-Time production to overcome the production-problems it had had in the past. In 1991, it took over a Swedish producer of wood-products, and after the privatisation of the Polish furniture-industry, IKEA took over three companies there in 1992 as well. This became part of a trend and every-time it had the chance, it would take over a supplier in Eastern Europe.

1991 onwards - also saw an IKEA expansion of stores in Eastern-Europe.

1992 - IKEA took over Habitat, a British retailer of furniture, that had previously caused a style-revolution in Britain. Until now, IKEA had not expanded to the UK, and it was assumed that it was Habitat's strength that was keeping it at bay. It was forced to sell, after expanding to France, Germany, and Spain, which had caused it to make huge losses. IKEA also used its presence in those countries as launch-pads, keeping Habitat as a separate brand.

1998 - China! Already having been a supplier of IKEA's since the 70s, and generally believed to be a huge opening market, IKEA opens its first store in Shanghai, through a joint venture with a Chinese firms. It was an exploratory step as the Chinese were not yet economically ready for the type of products the IKEA offered, though the assumption was that China's economy would grow 10% per year. IKEA wasn't competing on price either, basically being more expensive than any local competitor. Only after severe price-drops, did the business take off.

2000 - Russia. The company had already had talks in 1988 to open for business there, however the collapse of the Russian empire delayed that. Finally, based in part on Kamprad's gut-feeling, the decision was made. It was a good one. In year 2, the annual revenue was $260 million, making it one of the most successful expansions ever. 45,000 people applied to 600 vacancies in the first store. Due to high import-taxes of 28%, the decision was also made to start producing furniture locally also.

And everything else… is history.

Note that, as I used a single source for this time-line, a Dutch/German book on IKEA's 11 secrets, this blogpost cannot be taken as an ultimate authority on IKEA's growth-strategies. At the very least, I got some dates wrong.

Final thoughts

In my first post about IKEA's growth, I wanted to make clear that how a business expands is largely related to its origins. The relationship with Eastern-Europe is both due to a cultural proximity with that region, as well as Ingvar Kamprad's drive to lower costs. Germanic countries were also a logical step because of linguistic, and hence cultural similarities, as well as similar economic conditions.

Territories with which it was as yet unfamiliar, were being expanded into in a risk-reducing fashion, through franchising in Canada, China, and Australia, and later on in China, through joint ventures also. The acquisition of Habitat in the UK, could be perceived as a risk-reducing move also.

It is generally recognised that European firms are better at managing international expansion, simply because of the compressed experiences they get from growing in heterogeneous Europe, which makes them more flexible in other countries also. Still, you could see that certain culturally remote countries posed some difficulties, such as the US and China, and even the campaigns in Germany and the Netherlands did not proceed flawlessly.

All that aside, to me the most interesting part of all of this was IKEA's shift in strategy in the 90s, turning from being a retail-outlet to a producer-retailer hybrid. It is both a radical shift, but from what I understand, a very logical one.

That's it. Tomorrow, I'll publish some notes about the biggest pros and cons about IKEA's business.

The picture is a mash-up of the Evolution 101 podcast logo and IKEA's logo.

Filed under: Asia, business strategy, culture, entrepreneurship, Europe, Ikea, logistics, new business development, Research, retail, suppliers, supply chain managment, USA

So, I finally finished the book on IKEA, which, sadly, is NOT yet available in English, though there are other choices + I seem to remember reading that it will be released soon.

So, I finally finished the book on IKEA, which, sadly, is NOT yet available in English, though there are other choices + I seem to remember reading that it will be released soon.

In any case, a great book, which taught me a lot about the mentality that reigns inside IKEA, how logistics are organised, what determines design, what determines price, how people are managed, and… the most boring/interesting part: how IKEA evades taxes. That last one is really worth a read… they basically designed a complex financial structure, which enables them to offset tax-differences in various countries. As you may know the tax-levels in Sweden, its country of origin, are somewhat insane and have marked the company in a way that the Swedes probably didn't intend.

So what to do next. I'm a strong believer in making things actionable, vs. the passive digestion (& forgetting) of facts, and, in order to make this book useful, I need to do something about it. I previously thought about writing about the way that IKEA expanded internationally, as that sheds some insight into cultural differences of countries and the considerations a business has to make when launching there. It's also relevant IF you care about how the origins of a business determine where and how it will grow. I may still do that, but since it's a lot of work, I'll do it in note-form.

Something will probably come out of it. You can read about my previous coverage of IKEA here.

Next book: The Disney Way

While IKEA taught me about retail (and some extras), I'm hoping to learn more about how to organise entertainment. As I wrote a few days ago, a strong theme in my life is how to tell stories, in whatever form, but there is a whole process behind that and, while I have a rough view of what that is, I'm hoping that the Disney book has some practical tips.

I'll probably supplement this with The Toyota Way at some point, as I have a certain fascination for supply-chain management also.

Yes, yes, I read entirely too much…

FYI, previous book-reviews include:

- eBay's "The Perfect Store"

- McDonalds "Grinding It Out" here and here

- Starbucks' "Pour Your Heart Into It" here and here.

The picture is a mashup of this picture of a scary clown and this other lesser-known picture here.

Filed under: books, business strategy, Disney, entertainment, Ikea, interlude, management, retail

5 links - cool vs. tech, touch-screens, women, pizza, & bookstores

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 12:09 PMMan, I collected so many links, that I'll probably have to write three updates to cover the most important ones. We've got a lot of ground to cover, so let's get started. You can find my previous coverage on interesting links from the web, here, and my continuous stream of bookmarks, here.

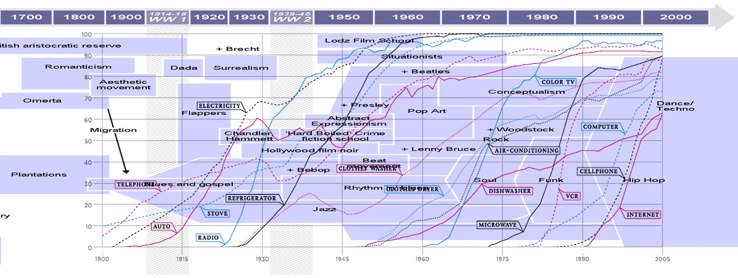

Link 1: On Magnetbox - Correlating cool with tech - With pictures like the one below, my work on this blog is really done. Interesting is the rise of computers vs. dance & hip-hop music (both of which are hugely benefiting from the cost-savings made possible by PC-based studios. (A note: low industry-barriers = high chance of suckage!). Also note the fall of art, after the colour TV was introduced. Kottke also made some comments about it.

Link 2: On BuzzFeed - Touch-Screen Ordering - BuzzFeed presents us with some stories about automatised ordering. There are both advantages and disadvantages, I think. Good is that it minimises errors in ordering and can interface well with back-office operations, such as ordering new supplies. It might also fit with the individualistic preference for self-service, I wrote about before. The disadvantage is the cost and the margins of error that information systems bring (I still shudder at the thought of the LAS disaster (pdf)) + the lack of the human factor. Martin Kunzelnick (German) links to some videos of Microsoft's Surface in a restaurant-environment.

Link 3: On Lightspeed Venture Partners - It is no accident that Typhoid Mary was a woman - Although it's a horrible-horrible title, and perhaps an obvious point, I've been coming across many stories about the social qualities that women possess, making them better at PR, marketing, sales, relationship-building. Something to keep in mind for any people-based business.

Link 4: On Reuters - Pizza Hut rolls out nationwide mobile ordering - A news-item (finally), and I'll probably delve into this topic sometime in the future. Arguably, Pizza Hut has been pursuing a different strategy from pretty much 98% of the pizza-restaurants out there. I'm sure that there is considerably brand-loyalty towards Pizza Hut, which will give it an advantage over delivering pizza-franchises, HOWEVER, it will probably be competing on price, which the franchise has not done so far. I'm not sure how that will affect their brand at all, but it's something to keep an eye on.

Link 5: On WSJ - Who's Buying the Bookstore? - arguably, there are few retail-outlets that evoke such an emotional response as bookstores. I find them comforting, and very similar to churches, in the way that it really is expected of you to be silent while browsing (on a side-note, I discussed a link of Dutch bookstore being opened in a church before). It's also a symbol of a community, as WSJ points out. Well, with competitive pressures from Amazon et al., these types of stores are clearly disappearing, or changing into hybrid monsters, which smaller stores can no longer compete with. WSJ points out a phenomenon related to that community-spirit, which is very touching. Capitalism isn't everything, particularly in places that target the softer pleasures in life. I'll have to reflect more on this, as I'm very attracted to these types of stores, and would love to set one up myself.

That's it, for this week. I'll see how I'll catch up on the rest of my links, but this went great (took 20 mins), and I always enjoy re-reading my bookmarks. I hope you do too.

Filed under: Amazon, books, business strategy, catering, community, culture, customers, design, food, horeca, innovation, Links, logistics, marketing, operations, restaurants, retail, technology, trends, vision

Hot or Not commercials - Axe's "Chocolate Man" vs. Eristoff Black

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 6:53 PMNothing to do with HotorNot's 20 million sale, which I just heard about today, I'm afraid. No, I watched Juno in the cinema today (great flick!), and saw following two commercials: Axe's "Chocolate Man," which was great, vs. Eristoff Black, which was not.

What I like about this short film is that it does give you a similar feeling to what it's like to walk around with a good scent and feel good about yourself. It's so hard to portray smell on video, I can imagine, and chocolate's just a great vehicle for it. The cinema-crowd's reaction was great also, laughing throughout the film.

*************

Update: apparently this is part of a whole viral campaign by Axe. I just found the matching game: Maneater

*************

In contrast…

I don't know about you, but this film just made me feel nervous. It's a commercial for an alcoholic beverage, ok, but nothing in the film suggested anything positive about the experience of drinking it. Instead you have this paranoid image of someone being locked in a glass sphere, pursued by bloodthirsty animals. Even the scene at the end, where it's a guy who apparently hit a shopping-window, is not reassuring, rather it confirms that this is a drink to be treated with caution. The cinema-crowd was totally not into this commercial either.

That's all from me this weekend. Have a nice one!

I've long been interested in the idea of franchising, though I'm somewhat conflicted about how to look at it. One the one side, it seems* like a relatively easy way to start a business, on the other side, it seems* a relatively cheap way to grow your business (*: within limits).

I've long been interested in the idea of franchising, though I'm somewhat conflicted about how to look at it. One the one side, it seems* like a relatively easy way to start a business, on the other side, it seems* a relatively cheap way to grow your business (*: within limits).

WSJ recently published an excellent study on high-performing franchises in the US. The choice of franchises is extensive, just like I concluded in my post on top-German franchises. At the same time, the most apparent choice, that of food, seems less and less attractive, and I quote from WSJ:

In particular, fast-food and casual-dining businesses, while still showing strength, with eight names on the list, also are facing pressure from wage and food cost increases. To lower operating costs, several food franchises already are shuttering some locations.Arguably, a business that is thinking about growing through franchising is faced with some restrictions. Writing a franchisees-manual is a scientific process, you'll probably have to restrict the complexity of operations so that they can be replicated, and there will still be some overhead related to managing the brand and some of the more problematic franchisees.

I think that it is that standardisation of operations, made big through the economies of scale so easily achievable in the US, that is bring competitive problems to chains, even to wholly owned ones like Starbucks. If your core-product is simple, and your business uses a simplified operation, then how hard is it for your competitors to replicate your whole business-model and -strategy in the long-term, really? It is only if your business strategy includes complex competitive advantages, such as extensive vertical and horizontal integration across the value chain, and/or if your business-model is based on "high-tech" components or processes, that you have a real chance of beating the clones. And to relate it to the rising operating costs, mentioned above, business with true competitive advantage can raise profit-margins or off-set the costs elsewhere, instead of having to close operations.

But ok, long-term strategic considerations aside, I see franchising is an attractive way to enter the business-world as an entrepreneur. The question of whether it's faux or real entrepreneurship, is not pertinent, I think. Considering that you have a wide range of choice of franchise-business opportunities, you'll still have to work hard to succeed, and the growth-opportunities can include starting multiple franchises also, it is not that different from starting any other kind of business. In my mind, I compare it to internet-entrepreneurship, which also relies on a large amount of free tools and distribution-mechanisms, but is still dependant on that special something for it to be successful.

What makes franchising particularly attractive, is the decreased amount of risk. According to a study in the Netherlands, 65% of franchises are still standing after 3 years. Compare that to independent start-ups, of which only 15% are alive at that time.

A large cause is, I'm sure, the level of support from the parent-company, which differ from business to business, and can include delivery of goods, marketing, administrative and IT services, made cheaper through centralisation. And they are frequently guided through the process of setting up and running the business, including legal advice. In exchange, they give away either a percentage of profits (ranging from 5 to 40%) or a set monthly sum to the franchiser.

The WSJ-article also lists the amount of investment typically needed to start a franchise. It ranges from ca. $5200 for an automotive company, to a staggering $1,3 million for a steakhouse. Of the 25 franchises recorded, only 5 received some kind of financial assistance (none of which in food). Another article at WSJ discusses some of the attitudes towards financing franchises, particularly during the current US-recession. Incidentally, another article in Dutch Elsevier magazine, sees franchising as an excellent way for businesses to grow during a recession, as it requires less human costs.

All in all, it is probably a safer way to start a business, though with all the points I made above, I don't think of it as 'light' entrepreneurship. There's clearly a lot of risk involved, beforehand, in terms of choosing the right franchise with growth-potential, financial risk to fund your business, market-risk, when you launch, and competitive risk, after your up and running.

I still want to discuss this topic further at a future date, particularly focussing on what its like to turn your own business into a franchise, and some other stuff related to buying into one.

The picture is courtesy of friendlyfranchising.com

Filed under: business strategy, entrepreneurship, Europe, finance, food, Franchising, human resources, innovation, management, new business development, operations, Research, restaurants, retail, trends, USA

My relationship with story-telling - a short autobiography part I

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 1:45 PMI'm in a philosophical mood today, after having spend an hour this morning sorting through the rough drafts for this blog (estimated at around 150), which I categorised as "idea," "rough notes," "feature complete," and "send it already." There were so many of them that I found myself a little overwhelmed to address a single one, a little afraid to miss seeing the forest through the trees, and instead decided to write about a core-principle in my life: story-telling.

I'm very attracted to the concept of telling stories. It's perhaps a little difficult to explain, but certainly related to the reason why I write so much, and also integral to what I want to do with my life.

When I grew up, I was reading all the time. From the back of cereal boxes, to encyclopaedias, to even the bible (which I thought was a great fantasy book). As a kid, I also remember building up cities in my room and garden, made out of toy-parts and characters, and constructing visual stories around what was happening.

I did not watch TV until I was 10, but, around that time, I fell in love with fantasy and sci-fi stories, both in book-form and on TV. I liked the way the story was constructed, and loved to imagine myself being there. I remember having magnificent visions of what I imagined the future of society, cities, and the home to look like.

Around 17, I decided to hold my first teen-party (the last one before that was probably around the ages 8-9). At that time, I was playing around in a band and very much into music-culture. I remember coming up with the party idea, which was essentially a visualisation of a club. It was lucky timing. We were just about to move and I had a huge house to my disposal.

The way I visualised it was to have rock-bands playing live in the living-room, a techno-room with a (borrowed, I think) strobe-light in the basement, and some other theme-related room elsewhere. Important were of course drinks and drugs, as, hey, I was 17. And equally important was the concept of complete freedom, which I think was communicated quite clearly.

A large inspiration was this video by the Prodigy - No Good (start the dance):

The end-result was great: around 50 people showed up, 2-3 bands were playing, and people did some crazy stuff, without getting me in trouble. In the end, I was still the one responsible, and took that seriously, but essentially everyone could do what they wanted. I repeated a similar party a few months later, which revolved around the same principles, with some restrictions, though around twice the amount of people.

That's where I'll end this. Lot's of stuff happened since then and will continue to happen, and I hope to write a second part in maybe 5-10 years from now (maybe sooner) about all the adventures I'll hopefully have, and evolutionary leaps I'll hopefully make.

Core to everything, I think, is vision and freedom. When you create a story, you have a vision of the components and the way they fit together into a dynamic process. At the same time, a story-teller must realise that his/her story is just the start for the listener/viewer/experiencer. It's a synergetic interaction between creator and beholder and the end-result can be both unpredictable and quite beautiful sometimes, a risk that, to me, is entirely worth it.

P.S. Happy Valentines day!

Filed under: About, culture, design, entertainment, horeca, humour, interlude, management, music, operations, retail, self-development, vision

Cracking impregnable fortresses - on the art of war and blue oceans

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 9:14 AM Every industry has a number of pains. Arguably, a problem in the FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) sector is that the market is saturated and that margins are fairly low. Over the next few weeks, I plan to take a deeper look at companies within the FMCG-segment for food, in order to understand the structure of the industry better, and the challenges faced by companies—new and existing.

Every industry has a number of pains. Arguably, a problem in the FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) sector is that the market is saturated and that margins are fairly low. Over the next few weeks, I plan to take a deeper look at companies within the FMCG-segment for food, in order to understand the structure of the industry better, and the challenges faced by companies—new and existing.

Somewhat related to this, I came across an interesting article at HBR, on "strategies to crack well-guarded markets," which I'll go into now.

I'm a great fan of the book "The Art of War" (not to be confused with "The War of Art," that I reviewed a few months ago…). Sun Tsu offers some timeless and broadly applicable tips on how to fight battles that cannot be won by force alone. The quote I remember best goes something like this (paraphrased):

"A big army is like water; it is fluid, it can envelop you, but it is also hard to control. Fight a big army like you would water, in places where it finds it difficult to move."HBR makes a similar point in their article (abstractly paraphrased to stay in character):

- Thread lightly - using a minimum of resources to enter these new markets also minimises the risk associated with these experiments.

- Be unpredicatable - when doing things fundamentally different from your enemy, you end up catching him off-guard and slow to respond.

- Use a dagger, not a sword - just like Sun Tsu's point about water, it perhaps makes little sense to use a bucket at the beginning. Instead attack there where it least expects it—via a market-niche—and start building towers.

- As well as a combination of any of the above

It reminded me to pick up the book, "Blue Ocean Strategy" again, which describes methods on how to find uncontested market-space, based on an analysis of existing products and companies and their shortcomings.

A pretty obvious example of this is the Nintendo Wii, which Jeremy discussed on Tech IT Easy some time ago, and which is reaching out to a whole new group of consumers, who traditionally not play console-/computer-games. Interestingly, the HBR-article looks at a related company, Jakks Pacific, which has also entered the console-market to compete with the big three, and has done so successfully by competing on price ($20 consoles) and marketing (working with big partners like Disney).

Other examples of Blue Ocean Strategies include Cirque Du Soleil v.s traditional circuses, which is a big inspiration to me personally, and Starbucks in the 80s-90s and on US-soil (!).

In the case of Starbucks, you certainly couldn't argue that their strategy is "blue ocean" in Europe or even globally today. However in the US, when they started, they targeted a niche demand for quality coffee, reshaped the value chain of a coffee-retailer, and initially grew through the acquisition of the Starbucks-brand and coffee-plant. Today the situation is somewhat different, Starbucks is the incumbent and its competitive advantage relies on finding new business opportunities. Whether they succeed, the future will show.

Any successful Blue Ocean Strategy depends, I feel, on the inability of incumbents to react—i.e. focussing on areas which incumbents are either neglecting or are finding it difficult to manoeuvre in. Starbucks is in a different business-cycle now, its novelty has worn off, and other companies can benefit from similar advantages in the value chain, such as sourcing quality raw materials and a huge demand in the market. I guess, to a degree, Starbucks' educational focus has created that market and given competitors a success-formula to emulate.

As mentioned, during the next few weeks, I'll be looking at other food-companies, particularly FMCG-ones, to get a better understanding of the industry and the challenges facing these firms. Who knows, maybe I'll discover some blue oceans…

The picture is courtesy of valuebasedmanagement.net.

Filed under: books, business strategy, coffee, culture, entrepreneurship, horeca, innovation, new business development, retail, starbucks, supply chain managment, trends

Building lifestyle-brands and the role that the internet can play

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 7:21 PM I'm a little distracted from blogging, I'm sorry. My current activities include a last-minute scrabble-play of my thesis, to make it a more logical read, and applying for jobs. And, not unsurprisingly, I'm having some writer's block as a result.

I'm a little distracted from blogging, I'm sorry. My current activities include a last-minute scrabble-play of my thesis, to make it a more logical read, and applying for jobs. And, not unsurprisingly, I'm having some writer's block as a result.

My post from a few weeks ago, about my anonymous friend, who's running a lifestyle-orientated business in a developing market, certainly opened my eyes to this area of the market.

Today, I'll talk about another company, Milner (cheese). There was an interesting article in Dutch marketing-magazine, Tijdschrift voor Marketing, on Milner's positioning-strategy from mass to lifestyle, which I'll discuss now, and which also lead to a post on Tech IT Easy about social networks as a strategic marketing-tool.

Milner = FMCG

Milner is considered a FMCG-company, that's fast-moving consumer goods, and falls into segment 2 on my food-industry map from last week. As I observed there also, this segment is usually the driver, if not always the conductor, of consumer-marketing.

The company is currently strongly present within the health-segment for cheese in the Netherlands, with over 50% market-share. This segment is also seeing between 60-70% growth from cheeses in general.

One thing that is clear for FMCGs is that margins are generally low (generally under 10%), competition is high, and as I made clear in my post on Tech IT Easy, features can easily be emulated by other companies.

Generating complex competitive advantages

The differentiating factor is the relationship the brand has with the consumer and vice versa. A brand that is designed for a lifestyle will generally have a much higher emotional value to consumers, than one based on features like cost or taste alone.

The logical conclusion is that those companies with deeper relationships to their customers will enjoy a higher competitive advantages over companies that do not focus on these relationships. And the complex nature of relationship is one that is difficult to emulate, hence giving companies a sustainable lead in the market.

But how to do that?

Paradigm-shift towards lifestyle

A lifestyle-product can be defined as a product that is built around the context of a certain group of consumers, resulting in an emotional value, as well as one based on features. This also has implications on the product-marketing strategies that a lifestyle-orientated company undertakes. As you may remember, the company my friend operates, still spends a considerable amount on marketing-activities after 2 years.

The theory that Milner cheese employs goes as follows. A great pain for food is health—which is really just an after-effect of the lifestyle people are leading. People are constantly looking for answers, so-called lifehacks, or more diet and exercise-related advice, all to regain power over their lives, minds, and bodies.

The key-issue is how to reach these customers. By addressing the pain that customers are feeling, by helping them live a healthier life, Milner is engaging in a relationship with its customers.

How does it do that?

How the internet fits into this

Traditionally, internet-marketing expenditure for FMCGs is quite low, around the 2% mark. Milner's budget currently assigns 10-15% to internet-marketing. It is able to do so, because it is already relatively well-positioned in terms of its brand and communication, so it feels more confident to experiment with new mediums.

As mentioned in my post on the food-industry-map, marketing to consumers is the responsibility of the consumer-goods-segment, however the degree that this activity is outsourced, depends on the amount of resources available to the company and the level of complexity of the activity. Arguably, both the novelty of internet-marketing to Milner, and particularly engaging into a relationship with consumers, make marketing fairly complex affair and the company did this via a third party, Advance, an interactive marking agency.

Advance set up a site called Je Beste Dag (translated: your best day), which advises visitors on how to have better days, based on a questionnaire they fill out. The first stage of the strategy is to build up a large mass of consumers that give out their email-adresses for further advice. Currently, there's 1 million people connected to the site. The second stage is to deepen that relationship, by encouraging return-visits and ultimately start a conversation.

It's both a time- and cost-consuming process for Milner. Essentially it is the sole sponsor of the campaign and has been running this campaign for nearly half a year no, without seeing any types of new product-developments yet. It is however working together with (other) marketing-agencies to develop its brands, which includes the design, positioning, quality, etc., as well as new product developments.

The interesting part of the whole process is that the majority of visitors already knows Milner, before even visiting the site. In other words, this clearly is an interactive marketing-campaign, which deepens the relationship between company and customer beyond the brand. Also, while the segment that Milner markets to via traditional channels, usually falls in the age-groups of 40-60, the age-group it is reaching now falls between 25-45, 60% of which don't yet have children.

Final thoughts

It is uncertain what exactly will come out of this. Milner is treating their internet-campaign as just another marketing-channel and holding Advance to targets it must meet. Which also allows them to measure its effectiveness. However, with a million young people connected to the site, and the communication-channels open, my gut tells me that they will be pretty happy.

The conversational aspects that the internet provides are certainly no surprise to the regular internet-user, however many web-companies are finding it difficult to generate sustainable business-models (e.g. Twitter / Facebook). As I made clear in my post on Tech IT Easy, I think these kinds of marketing-campaigns open up some possibilities there.

Filed under: branding, business strategy, e-commerce, Europe, food, Health, marketing, media, Milner, new business development, retail, suppliers, trends

I'm still following my tradition of looking back at what I covered and processing it into a blogpost. The general aim is for me to process the stuff I wrote about before, and give a reader some compressed value of an otherwise unforgiving linear medium. Time waits for no-one.

I'm still following my tradition of looking back at what I covered and processing it into a blogpost. The general aim is for me to process the stuff I wrote about before, and give a reader some compressed value of an otherwise unforgiving linear medium. Time waits for no-one.

Why did it take so friggin' long?

For Months 1 & 2, I did so on a monthly basis. Later on, I was interrupted for study-related reasons, so hereby a 3 month summary (though only about 6 weeks of real activity).

Now, if month 1 can be categorised as a focus on market research, design, core-values, the value chain, and trends in FnR, and month 2 on human resources, business strategy, branding & marketing, innovation, and finance, months 3-6 aimed at news & trends, operational issues, marketing & branding, entrepreneurship, and strategy. Phew, what a mouthful… this is going to be a long post, so let's get started.

Micro-topics

Following three headings cover, what I call, micro-topics. They delve into specific situations (news & trends) or issues in running a business (operational, branding & marketing).

News & Trends

I noticed a decreased focus on news these months, simply because I didn't want to re-blog other people's stuff, and found conceptual lenses, and micro-topics more interesting. Also, my links often covered some news, as do my continuously updated bookmarks.

Nevertheless, I tried to identified some trends, namely private labels, organics, and SEPA, which I discussed at some greater depth. For Private labels, I looked at what regions and product lines were doing best, and came to the conclusion that there's huge potential in terms of lifestyle-products and offering higher quality goods than manufacturers can, simply because of the savings in marketing. I discussed lifestyle in a number of other posts, but I will go into those later on.

For organics, which has seen a huge upsurge in the last 5 years, I remain bearish, simply because I see it as a very inefficient, resource, and human-intensive process, that, in combination with the high energy-costs and rising food-prices, may not appeal to consumers increasingly shrinking wallets. That said, innovations are usually inefficient at the start, organics fill a certain need, and more automisation in such production-methods may dissolve many of my arguments.

I also looked at SEPA—the single European payment area—which was just launched (and you should be seeing an option to pay via SEPA in your internet-banking site now). Arguably the most boring post, I've ever, ever written (well, there are some contenders), but since I want Europe to be a single market so that businesses can finally benefit from the same economies of scale as the US, China, India, and Brazil, I thought it be important to discuss it.

Microscopically, and just for fun, I also identified some trends in terms of cinematics, beers, and pie, as well as a changing perception of expertise (more on this when I discuss entrepreneurship later on).

Operational

A second focal point was on operations of food & retail-outlets. I'm fascinated by optimising internal processes of businesses, so one of the topics I focussed on was whether it would be possible to use lean Toyota principles in a Food / Retail environment. I think it is, but at the same time, should not act as a replacement for customer-service. Granted, competition is fierce and any cost-savings should be welcomed, but the differentiating factor should be the amount of cherries on top: service-quality, product-quality, etc. I still need to read the book, though, and I definitely have more to learn/write about this subject.

I also looked at real-estate, fairly extensively, though some topics for future exploration remain. Clearly one of the biggest pains for FnR-venues is location, location, location… (it is also an inherent strategic component to large franchises like McDonalds) and I started with looking at structuring search and using checklists. In a second post I looked at the competitive/cooperative context of choosing a location, and in the third post, I looked at a number of costs that are part of the location choice.

Marketing & Branding

M & B is a continuous micro-topic of mine, even though I don't consider myself a marketeer. Two of my favourite topics include "the service paradox - on self-service and customer-rentention," which discusses the strangely liberating effect that no service has on today's individualised customers and positively affects their loyalty in return… talk about an eye-opener, for me at least… and "Lifestyle products - the costs of educating a market," which looks at the significant marketing-costs associated with starting a company in an unmapped market. As for the latter, I'll definitely be writing more about the particularities of lifestyle-products pretty soon.

The other three topics were interludes—hence the reason why I don't consider myself an expert. I wrote about how much of marketing is based on arguments, how arguments are often designed to distract or confuse an audience, how the consumer is overwhelmed with them, and how their value is ultimately decreased drastically. Very abstract… I also proposed that this is exactly why simple products work exactly so well: kill the argument.

Two more interludes include a review of Malcolm Gladwell's books, which both offer great insight into how people think (and how to market products), and I re-blogged "a marketing plan in a nutshell," kindly provided by an MBA-student at MeFi, which should be useful as a general reference.

Macro-topics

Following are topics that are core to what I write about: entrepreneurship and strategy. The first aiming at starting, running, and growing FnR-related companies, and the second at the bigger picture: taking an industry-perspective, how to interact within the context of a value-chain, core-pains, etc. There is also considerable overlap between the links I discuss now and those that came before.

Entrepreneurship

Looking at my eship-posts, I found that I often take a more personal stance at issues, compared to other disciplines. I think that's related to that the human element is stronger in these businesses, something I found out from speaking to many start-ups, incl. ca. 300 start-ups for my thesis.

In "The business of HoReCa - Hotels, Restaurants, Cafes," I discuss the issue of semantics in regards to choosing a vocation, and the perspective of my father, who helps me think about this area a lot. This is somewhat contrasted by my post on my own generalised (vs. specialised) look at the food & retail-industry, in the sense that I care more about the big picture (for now at least). I'll come back to this in the future, I'm sure.

In my post on "lifestyle-products," which I mentioned before, I also try to approach the topic of starting such a business in a second-world country, through a friend's eyes. Similarly, my post on "How being in the right place at the right time translates to starting a business," takes a very personal, and perhaps subjective approach to the issue.

Some micro- and just-for-fun topics include the "10,000-hours-to-be-an-expert rule," in which I identify a trend that's pretty similar to crowdsourcing expertise. On Tech IT Easy, Georgia Psyllidou discusses a similar phenomenon about how people can find work nowadays, and I think I will approach this topic again in the future. Call it semantic, crowdsourcing, open innovation, etc., but the world is changing, it is getting flatter, which has both implications to finding human resources, as well as distributing knowledge. For instance, in a recent article on HBR, the topic of authentic leadership is discussed entirely from the perspective of 1000s of examples. Worth a read and thought-inspiring!

Another fun topic was the Lowest Common Denominator (LCD). I first approached this abstractly, while under thesis-stress, but I find it a useful way of thinking about simplicity of action. What is the simplest, most basic feature that your product needs, that your strategy needs, that your company needs to work? Later on, I explored this again concerning my friend's lifestyle-business.

The strategic lense

Strategy has always been difficult to conceptualise, I felt, because there's strategy to everything—war, running a business, running your life, getting the girl, etc. That's perhaps the reason why I never got around to writing a thesis for it, and chose entrepreneurship instead.

I discussed IKEA a number of times in my blog, and one strategic issue I approached, were the early years of growth for the company. My philosophy concerning business is that, generally, "where you are from and when you are from matters a great deal to where you are going," and the same applies to IKEA. Of course, IKEA went far beyond Scandinavia, and I hope to get around to discussing the later expansions the company went through.

Amazon & Jeff Bezos was another topic, in which I wrote about Amazon's approach to innovation (very customer-focussed) and Bezos' transformation from entrepreneur to CEO (from micro to macro, challenging for many).

Another topic was the growth strategy of Starbucks (wholly-owned), vs. that of Subway's (franchise), which is clearly receiving a lot of flack these last months. In the article, I commented on some of the reasons given by other smart people, about why these strategies differ. Some good economical reasons were given, however, none, I felt, went into the roots of the issue. Two factors affected Starbucks' strategy: the roots of the business and the roots of the founders.

Somewhat related, a few weeks ago, i discussed the intriguing strategy of Metro-Group, which has placed two electronics-chains into the European market, Media Markt vs. Saturn, seeming to everyone as competitors. Turns out they are the equivalent to a franchise-system (though certainly a more complex one than Subway), which I think are meant to saturate the market.

Some just-for-fun topics included another post on the lowest common denominator, which I felt was a good lens through which simple strategies can be designed; two posts (1 & 2) about big pains the food-industry is feeling (and which ties into my post from yesterday; and why fitness studios are employing such restrictive contracts, which I felt was caused by either an inelasticity of demand or because they were in trouble.

Clearly a number of other topics fit within the strategic paradigm, but I'm not going to discuss them here.

Wrapping up

What about those Sounds?

I'm considering dropping the "Sounds" from S+FnR, however, it is still a very strong topic in the back of my mind as I'd like to work in venues where people dance… No, seriously. The way I'm looking at it is that I have to focus on certain basics first, and music & media will eventually pop up. So the title stays as it is.

Final thoughts

The nice thing about blogging is that you can measure your progress. I measure them both by readers, by feedback, and by my own perception. During the first months, I was very much in the dark about this industry, and to a degree, I still am. But I notice that things start making more sense, there is a certain logic to how processes work, why certain business models are chosen, etc. So, mentally, for me, there is a certain growth and I hope I can continue at that rate in the future.

I'm still on a certain trajectory in my mind, regarding the amount of secondary and primary activities I have to do to reach new levels. On the latter front, I definitely have a much better idea of where I want to go, after having blogged/thought/discussed about these topics for so many months.

That is all! I can enjoy my weekend, enjoy yours, and until next week.

Filed under: About, branding, business strategy, eco-trends, entrepreneurship, Franchising, green, horeca, marketing, Monthly recap, private labels, real estate, retail, supply chain managment, trends, vision

I'm currently working on a wrap-up of what I wrote about in months 3-6. It's usually a monthly tradition (see months 1 & 2), but this one is extra long and taking me some time. Apologies for the silence this has been causing this week.

One of the things, I'm working on is a work in progress, a map of the food-industry. Step 1 is to identify the individual segments, which, I should note, are probably transferable to a great number of industries. Future iterations will include identifying specific companies in each segment, as well as sub-segments, and specific segment-pains also.

- Segment 1 - the production of raw materials: This can involve anything from growing coffee-beans, to potatoes, to rubber and trees (later used for packaging). Some vertical integration with segment 2 and perhaps 3.

- Segment 2 - the production of consumer-goods: The activities here involve sourcing raw materials and producing them into goods, ready for retail. From my understanding, there are a number of super-producers (Unilever, P&G, etc.) and more specialised ones. Some vertical integration with other segments, plenty of horizontal integration also.

- Segment 3 - retail: A diversified segment, consisting of super-markets, specialised stores, and hybrids (which combine retail with other services like music, etc.). Some vertical integration occurring, with e.g. private labels, and large franchises like McDonalds & Starbucks that communicate directly with segment 1.

- Segment 4 - consumers: too diversified for me to summarise at this stage. What I do note is that the reach of customers is increasing up the value chain: organics, enviromentalism, etc. are all signs of this.

- Sub-segments - marketing & logistics: It has been my observation that the degree that these are externalised depends on the resources available within and the complexities of the tasks. What I also noticed is that it's the supplier, not the buyer, that takes care of these things. And finally, that it's segment 2 that is usually responsible for marketing their products to segment 4, the consumers. I expect that something similar is or will be occurring from segment 1 to segment 4, to address concerns consumers may be having about production-methods.

- Meta-segment A - regulation: It has been my observation from my thesis that the government is a factor at pretty much every stage of the process of bringing a product to the market. It is a tool both for consumers, for larger interest-groups, and for businesses to stimulate change within industries, with all the consequences that has. Again, regulations pertaining to organic & green production-methods, as well as human rights and memberships of trade-unions are just a few of many factors to consider here.

- Meta-segment B - optimisation: This is where I would place consultancies, which are super-specialists aimed at improving processes in and between organisations, but also aiming at customers who are having more and more information at their disposal, more cash, and more complex needs.

I'm hoping to finish up my wrap-up by this weekend and that it will be business as usual next week.

Filed under: business strategy, customers, eco-trends, green, logistics, marketing, Research, restaurants, retail, subsidies, supermarkets, suppliers, supply chain managment, trends

What's the biggest pain in your industry II - Carbon emissions

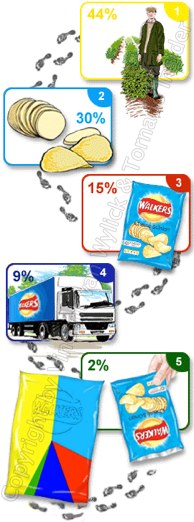

0 comments Posted by Unknown at 11:17 AMContinuing from part I - obesity, this post will be equally light as I have "♫ my mind on my money and my money on my mind… ♫" Or something to that effect. According to a carbon-emission calculation of PepsiCo's Walkers crisps, the majority of carbon emissions come from the production of raw materials (44%) and processing thereof (30%). A Dutch magazine, Tijdschrift voor Marketing, attributes the majority of the carbon footprint to transportation of said materials, and forms the conclusion that more and more production and consumption has to happen on a localised scale.

According to a carbon-emission calculation of PepsiCo's Walkers crisps, the majority of carbon emissions come from the production of raw materials (44%) and processing thereof (30%). A Dutch magazine, Tijdschrift voor Marketing, attributes the majority of the carbon footprint to transportation of said materials, and forms the conclusion that more and more production and consumption has to happen on a localised scale.

Even though the makeup of those figures may be open to interpretation—there is no breakdown about what in the first 44% is due to actual farming and what to transportation—perhaps, Mr. Kuiper, the author of that piece, has a point.

In a TED-lecture, James Howard Kunstler argues that the 'hydrogen-economy' is a pipe-dream and we must start thinking about creating urban environments fully equipped with the means of production, transportation, living, and waste-disposal, all in one. Very inspiring, though clearly requiring significant paradigm- and resource-shifts from today's globalised economy.

Clearly transportation comes at a cost, the question is how much the alternative would cost. Building super-farms, creating artificial climates to grow exotic food, waste-disposal, dealing with virus-outbreaks—regarding the latter, farmers already have problems dealing with chickens, sheep, and cows now, let alone having to deal with something like Kunstler's utopian vision—all of which represent costs that have to be accounted for.

But, I don't want to sound like a pessimist. I actually love the idea of a super-farm and a super-urban environment, regardless of the monetary cost. I'm sure plenty a sci-fi artist has tried to draw such a very thing (as have I). It's complicated, expensive, but exciting at the same time.

Asking you a tough question: How would you do it? What would a Kunstler-inspired localised economy look like to you? Is it even possible? … well, something to think about anyway…